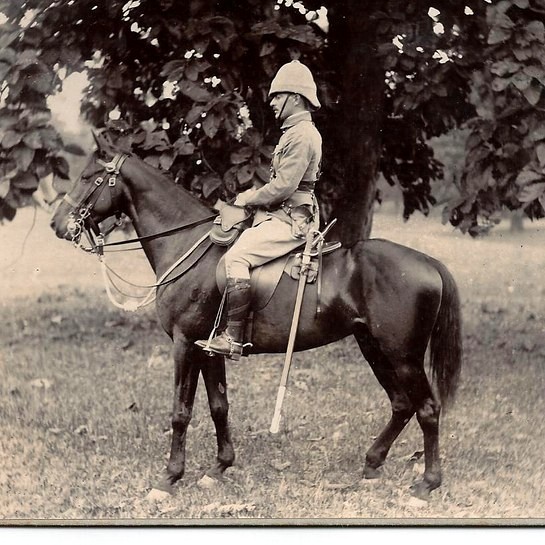

Mounted officer wearing khaki drill frock, Sam Browne belt rig, foreign service helmet and pantaloons tucked into Stohwasser gaiters. (Photo: James Holt collection)

Throughout the Twentieth Century, the world’s Super Powers have waged war against a sometimes seemingly invisible, highly mobile enemy. An enemy familiar with the lands he defends and what it takes to survive in them. France and later the United States struggled through Viet Nam and the former Soviet Union endured the hardships offered by Afghanistan. At the dawn of the Twentieth Century Britain ventured into South Africa. The campaign that followed was an omen of how war would be waged in the new century. A tree of terms we are all too familiar with now has roots embedded on the Veldt of South Africa… commando, guerilla war, trenches, machine gun, barbed wire, and sadly concentration camps.

Within the British army of the time, there were continuing struggles between traditionalists and reformers. Many officers still believed mass volley fire and the bayonet would carry the day. Kitchener’s re-conquest of the Sudan in 1898, particularly the battle of Omdurman, was a stirring example of Victorian textbook tactics that stood to reinforce popular beliefs in those tactics. The South African war stands as a watershed of those beliefs. Queen Victoria’s soldiers were up against an enemy that had equal, if not superior, firepower. The Boer was highly mobile, skilled at field craft, and an expert marksman. All attributes of a successful hunter. Not just the ability to discharge a weapon at a stationary target, but the skill to single out a moving target at distance and take it out of action. Many British officers fell victim to this accuracy simply because they could be singled out.

Lieutenant Harry Lumsden was the first British officer to provide his men with a practical working garment. In 1846 while on service in India Lt. Lumsden of the Corps of Guides began the process of dyeing the white cotton working garments with mud. When dried they blended in with the surrounding landscape. Men wearing these dust colored garments would fight subsequent campaigns in India, Afghanistan, and the African continent. Dyeing of the fabric took place using various local methods until 1884 when chemist Frederick A. Gatty patented a fast curing dye that would eventually be used in the manufacture of the Uniform for Active Service. “Khaki,” the Hindi word for Dust, would finally be accepted as the color of uniforms for active service in 1896.

Infantry officers serge frock as per Dress Regulations for Officers 1900, made exactly as the cotton drill version with the exception of larger seams to accommodate the thicker material. The serge for both officers and men was warmer and more durable than the cotton drill frocks. His white foreign service helmet has a separate khaki cover and puggaree which bears the regimental flash of the Shropshire Light Infantry, (white worsted embroidery on a red cloth backing). His double brace Sam Browne belt would carry his revolver and sword. Strung over his shoulders, haversack and private purchase water bottle. (Photo: James Holt collection)

The loose fitting khaki frock worn by officers was made of khaki dyed cotton drill or serge material and styled after the blue patrol jacket. (The color of the serge version varies greatly from khaki to a dark drab color with various shades in between). White linen collars were an option for officers and were buttoned into the collar of the frock. The frock had two pleated breast pockets, two shoulder straps, an internal waist belt and two lower pockets in the skirt of the frock. Two diagonal pleats on either side of the collar running diagonally toward the outer edge of the breast pockets and three pleats to the point of each cuff. Five regimental buttons secured the frock. The doublet for highland officers was of the same cotton drill or serge material used for frocks of English officers. Cutaway skirt fronts and gauntlet cuffs being the most notable difference. Many doublets had breast pockets with dual button closure. These buttons were covered in the same cotton or serge material as the doublet. Most highland officers observed in photographs of the 2nd Anglo Boer War have scalloped pocket flaps with single button closure on their breast, and lower pockets on the skirt of their doublet.

(I use the term “drill” throughout this article in reference to the weave of the cotton material used in construction of frocks, doublets, and helmet covers.)

An impressive officer of the Seaforth Highlanders wearing a drab serge doublet and breeches. Note the double button closure of the breast pockets. (Photo: James Holt collection.)

Trousers worn by officers were of khaki cotton or drab serge material with foot straps of black or brown leather. Khaki, whipcord, or serge breeches were also worn, while some highland officers wore kilts.

Assorted officers foot coverings of leather ,canvas and cloth. Dark blue Royal artillery puttees and khaki infantry puttees by Fox. (Photo: James Holt collection)

Footwear varied in the field but typically consisted of brown or black leather ankle boots. For mounted officers knee boots, butcher boots or hunting boots were popular choices. Worn over these would be a variety of lower leg protection. Stohwasser gaiters, cloth puttees, and various other types of leather, cloth, or canvas gaiters. When wearing their kilts highland officers wore ankle boots, khaki canvas spats, hose and garters. Khaki kilt aprons were also provided for officers and men. The kilt aprons were adequate enough for troops on the march but offered minimal concealment to a soldier in the prone position.

Officers on active service were able to purchase the recommended field equipment from various Army & Navy outfitters. This typically consisted of a double braced Sam Browne belt rig with holster, ammunition pouch, and sword frog. Further to this was added a haversack, water bottle, revolver, and sword. The great coat was carried from a khaki webbing sling and held rolled in place by two buff leather straps. Some Sam Browne belts had provision on the back of the shoulder straps to attach the haversack. Although a very practical way for an officer to carry his kit, the Sam Browne was the mark of an officer, on the veldt they became the target of many a Boer marksman.

Alternative headwear worn by some officers. L-R: Staff officers visor cap, khaki field

service cap, officers Torin cap. (Photos: James Holt collection)

A Captain of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders as he might have appeared in South Africa 1899-1902. He wears a khaki drill doublet with gauntlet cuffs, helmet with khaki 6 panel cover and regimental badge or “flash” on the left side consisting of an o/r’s collar badge on a red Melton cloth backing. His beautiful honey colored Sam Browne belt, haversack, water bottle are all provided by Hobson and Sons, and his helmet is by Hawkes & Co. (Photo: James Holt collection)

Rear view of a Sam Browne rig displaying haversack and greatcoat as carried by officers. (Photo: James Holt collection)

Officer’s foreign service helmet worn in South Africa by Capt. William H. G. Kemmis 4th Vol.Battalion South Wales Borderers. Khaki covered cork with muslin puggaree. The flash is a leather backed red Melton cloth with the individual letters sewn to the backing. (Photo: James Holt collection)

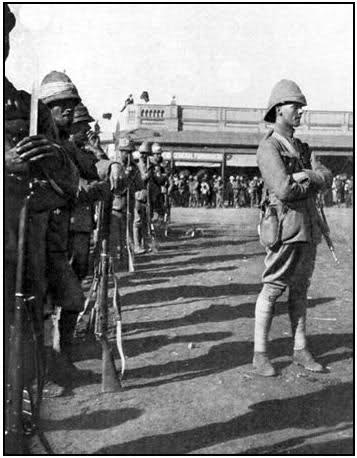

The Grenadier Guards in Pretoria. Photos of Guardsman serving in the Boer War are often show wearing white, or lighter colored puggarees around the crown of the foreign service helmet. Note the officers’ private purchase water bottle and carbine. (Photo: Black and White Budget James Holt collection)

With the high casualty rate of officers suffered in the early stages of the war, officers started adopting the appearance of the rank and file. Many adopted carbines or rifles, and began wearing the valise equipment of the ranks. The sword, being useless in the type of mobile warfare that prevailed during this campaign, was abandoned and in many cases the revolver was retained. Buttons were “browned” or dulled. Rank insignia was given the same treatment or removed entirely. The foreign service helmet remained the headgear of choice for officers over the increasingly popular Wolseley helmet that was an officer mainstay in the Sudan campaign of 1896-1898. The influx of the Imperial Yeomanry serving in South Africa, along with Colonial units, saw the slouch hat begin its rise in popularity as a very practical piece of headgear in warm climates. Made of felt and well ventilated it could be worn with the brim up or down, and afforded the wearer a most comfortable and lightweight form of headgear.

Grenadier Guards Officer’s serge frock. This serge frock bears evidence of a rough campaign life with its numerous field repairs and staining. The sleeves are lined in a lightweight flannel for additional warmth .He wears the pattern 1888 Valise braces and belt with Mk.3 ammo pouches. His private purchase haversack hangs from his right shoulder while strung over his left is a private purchase water bottle with buff leather strap and cradle to better assimilate the “look” of the ranks. His whistle being the only real indication of his status. The Hawke’s & Company foreign service helmet is khaki with a loosely wrapped white puggaree. Officers’ frocks of the Guards Regiments of the period had the buttons spaced according to seniority of the regiment, ie, Grenadiers in a single line, Coldstream in pairs, Scots in threes, Irish in fours (Photo: James Holt collection)

For comparison: The smooth cotton frock on the left was worn by Captain William Murray-Threipland 3rd Battalion, Grenadier Guards, Sudan 1898, South Africa 1899-1901. A stark contrast to the late war appearance of the officers serge (and kit) on the right. Threipland later became the first Commanding Officer of the Welsh Guards, upon their formation in 1915. (Photo: James Holt collection)

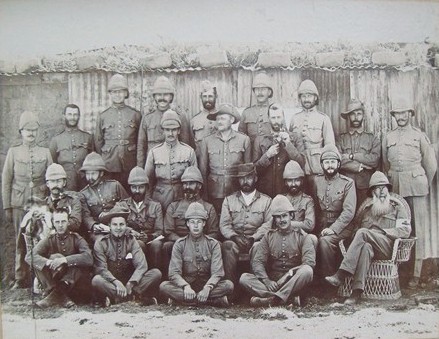

3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards at the Modder River 1899. Thriepland is standing at the right wearing the Woseley helmet and the khaki frock pictured above. The officer standing center wearing the slouch hat has rank stars (x2 denoting Captain) pinned to the upturned brim.( Photo: James Holt collection)

Officer’s four pocket serge frock of the Imperial Yeomanry. Five bronze Imperial Yeomanry buttons secure the front of the frock while a pair of bronze IY shoulder titles adorn his shoulder straps. He carries field glasses, private purchase haversack and one of many types of private purchase water bottles available. The felt slouch hat is made by Thomas Townend and Sons. Stitched to the crown of the hat, hidden by the upturned brim, is a brass holder to accommodate his Emu feather plume. (Photo: James Holt collection)

Officers serving with the Imperial Yeomanry adopted a four pocket frock of khaki or drab serge material. Though two pocket versions are not uncommon. Early war Yeomanry units also wore the foreign service helmet but many more adopted the slouch hat. Rank was worn in the same manner as Regular serving officers, a combination of “stars and crowns” upon the shoulder straps of their service frocks. Accoutrements would be purchased from the same sources as their Regular counterparts, though more variety would be observed within the Yeomanry units themselves. The Queens Westminster Volunteers surrendered much of their equipment to the ranks of the City Imperial Volunteers!

A pair of officers’ slouch hats. Both are made of felt and have a leather sweat band and chin strap stitched to the interior. The hat on the left bears the collar badge of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) while the hat on the right has the standard rosette of the Imperial Yeomanry. (Photo: James Holt collection)

Copyright © 2012 James A. Holt

Many thanks must go to Stuart Bates for his prompting me to prepare this article. His keen advice and academic eye are not to be overlooked either. Your enthusiasm is contagious. And thanks go to Benny Bough without whom this presentation would not have appeared at this time.

Sources

- Absent Minded Beggars. Will Bennett

- The Boer War, Uniforms Illustrated No. 19., P.J. Haythornthwaite

- The Boer War. Thomas Pakenham

- British Infantry Uniforms Since 1660. Michael Barthorp illustrated by Pierre Turner

- The Black Angel: The Volunteers of the Border Regiment in the Boer War. By Colin Bardgett

- Dress Regulations for the Officers of the Army 1891

- Dress Regulations for the Army 1900

- The British Army from Old Photographs. Boris Mollo

- Life of an Irish Soldier. General Alexander Godley, G.C.B, K.C.M.G

- Oxfordshire Light Infantry in South Africa. Compiled from various officer accounts and diaries. Eyre & Spottiswoode 1901

- Buttons of the British Army. Howard Ripley

Any use of the photos or their descriptions from the Holt collection, by printed or electronic means, without the express written consent of the author James A. Holt, is prohibited.

James A. Holt.

Outstanding article. I learned quite a bit. I am proud of the author.

Very interesting piece Jim, with superb photographs, thanks for the article,

first rate article

i loved reading this article.

I am one of William Murray Threipland’s grandsons (note unusual spelling) and have more photos of him. A couple of small points; how did you get hold of his uniform – very fascinating? (Did you buy it at a sale of my brother’s effects at Fingask Castle some 25 years ago?) I have other photos of ‘Bill’ as he was known in the family, one sitting among other officiers with – I think- General Roberts. Of interest to you?

A real pleasure to hear from one of Threiplands’ ancestors. The cotton frock did originate from the Fingask Castle sale, though I purchased it through Bosley’s in 1994 or ’95. There were also several other pieces sold off that did not make it to the Bosley’s sale. One of which I believe is the serge frock pictured above along with the positive I’d frock. Both are hand sewn, identical in size, and appear to be sewn by the same person. The second frock also came out of Fingask Castle as conveyed to me from the individual I bought it from. He, having no idea of me owning the I’d frock. Simply stated as bought at an estate sale at Fingask Castle.

I would be interested in seeing the picture you mention. By the way, “Bills” slouch hat is on display in the Guards Museum, London.

Hi this site and information is excellent. I am currently researching the ww1 roll of honour at all Saints Church Higher Walton and the Gatty Dyeworks. I’m writing a book about it and having an exhibition at the Church 7th to 9th November 2014. I was wondering if you would be kind enough to allow me permission to print your pictures and information for the exhibition and use the black and white image for the book. They are some of the best pictures and descriptions I have seen……and I have seen a lot!

Of course I will credit you and put a link in both the book and on my Facebook page to link to your site.

I look forward to hearing from you. My email starts with a lowercase s not a capital!

Thank you

Sarah yates

Thank you for your interest, and the kind words Sarah. Respectfully, I must decline to participate in your project at this time and deny the use of my material/photos etc.

Good luck in your endeavors.

James

But great care must be exercised when working with it.

Zac has learned leadership in non conventional ways and I suspect that he will achieve his Life’s Work

in an out-of-the-ordinary way. Take cardboard boxes

ashore to the dumpster as soon as you’re done.

Hello dear sir

We have seen your side

Which is very beautiful hats, but my mail properly so kind of you to read and follow the corrupt,

military caps we make ourselves the way we build custom hat you can set up our own. We affordable and good quality will make the

If you agree with me that you do business with us will have good profit

We give you the chance to see the quality we’ve come

Once again I say you do not understand my jokes that are going to benefit you

You sent us pictures of their hats and took us first to check rates were rates if you wish to work with us

I have attached a few pictures are sending you see it

Our Contact Details as follows

Awaiting for positive response….

General Manager

BOOSTER INDUSTRIES.

Mr. Asif Khush

Hello Mr.Holt, I was looking through your photographs and would like to point out an error in description. The photo of 3rd.Grenadier Guards with Threipland standing on the right is incorrect. If it is definitely

W Murray Threipland then the photo must be 2nd.GG. If it is definitely 3rd.GG then Threipland is not the individual on the right. He was i/c 2 company 2nd.GG which was not at Modder River. I have an original photo of officers and NCO’s of 2nd.GG, taken in 1900 in which Threipland can be seen in the group. I hope this information is of use to you.

Hello Sir,

Wonderful article! I have always found the patterns of Victorian Uniforms very interesting and far superior to uniforms today. Do you happen to know of anywhere where I would be able to obtain patters for uniforms such as these? Any help would be gladly appreciated!

Respectfully, Grady W Owens

What a super article! So many uniform publications are skimpy on the Boer War and so unclear on colours- particularly the appearance of khaki serge and khaki cotton.

I’m trying to piece together some of my family tree, and have an old sepia photograph (bad condition) in which there are two men in uniforms. I figured if I could identify the uniforms it might be a start…. I’d appreciate any help from anyone….

A Question , the Victorian Blue round water-bottle that was used by the Brits in the second Anglo Boer war , was it also used in the Anglo Zulu War ? I have seen exhibited wooden water-bottles from the Anglo Zulu War and the round Blue water bottle, so was the latter also around in 1879 alongside the wooden one’s , perhaps just officer’ water-bottles?

A Question , the Victorian Blue round water-bottle that was used by the Brits in the second Anglo Boer war , was it also used in the Anglo Zulu War ? I have seen exhibited wooden water-bottles from the Anglo Zulu War and the round Blue water bottle, so was the latter also around in 1879 alongside the wooden one’s , perhaps just officer’ water-bottles?

Please more info on the Anglo Zulu war verse Anglo Boer War white Pith/ khaki pith / difference in Martin Henri etc much appreciated