Here the term ‘Desert Goggles’ is taken as those goggles which seem to have been issued to British Empire Troops specifically for use in desert campaigns in the late 19th to mid 20th Century. These goggles differ from the more ubiquitous; dust; general purpose; transport; tank; dispatch rider; mountain and snow goggles issued from mid-WWI by most nations, in being campaign specific. The three main goggle types discussed here were used in the Sudan (1882-98); the Mesopotamian (1914-18) and the North African (1940-43) campaigns respectively.

The ‘Sudan’ goggles have been usefully discussed on several relevant forums (see References), as have the ‘Mesopotamian’ goggles, however, the ‘Mesopotamian’ and ‘North African’ (or SLM) goggles have usually been assumed to be virtually identical, apart from the 1940s date stamp on the latter, here however, it appears that they were in-fact quite different, although some transition types may exist.

The ‘Sudan’ goggles

Arid deserts are dusty, bright and often fly infested places. All three factors cause eye problems for people venturing into those areas. Various veils, masks and headdresses have been used for millennia in an attempt to relieve these problems.

As early as 1885 during the Sudan Campaign these problems were addressed by the decision to issue goggles. Sir Garnet Wolseley, who in the year 1862 had been an observer of the American Civil War may have witnessed the use of railway ‘cinder goggles’ there. In 1882 he was made ‘Adjutant-General to the Forces’ in Egypt and it is thought that he was instrumental in the adoption of ‘cinder goggles’ due to his Civil War experience. It is not known if the goggles issued to British troops were US imports or whether they had been put into production in the UK; but they do seem to be exactly the same as the 40 year old US railway/civil War type.

Figure 2. A provenanced pair of ‘Sudan goggles’ from the Edinburgh Castle Museum, 1st Battalion, Scots Guards (Ref. 2.). The cups are made of fine wire mesh formed into a hemispherical tear-drop shape. Simple tie-up straps attach to a remarkably small metal eye on the temporal point of the soldered cups. The bridge is a small chain covered in a tube of cloth; crude adjustment is possible by adding or removing links. They were issued in an oval soldered sheet tin container, clear lacquered on the outside.

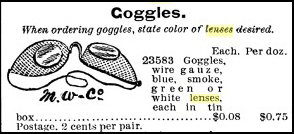

Figure 3. A late 1800s US advertisement for the type. Made by M.W.Co. Only 8 cents each! This is ten times less than other goggles advertised on the same page and may imply they were government/railway surplus?

In the 1880s there were not many goggle types to choose from; up until the early twentieth century glass was not as we know it today, it was very brittle. As such the wisdom of putting pieces of it less than an inch from One’s eyes was not axiomatic; unless for ophthalmic reasons. As a result glass eye protection at the end of the 19th century, in situations where it might be struck by hard objects, was rare. Back in the second quarter of the C19th small glass ‘Railway spectacles’ and ‘cinder goggles’ had evolved (the former in France and the latter in the USA), from the common tinted plain glass spectacles used internationally as sun glasses. The Railway Spectacles and Cinder Goggles were for use on the footplates of steam trains and for passengers in open carriages. Wind, smoke, soot and small cinders, however, were the only hazards expected. Horse transport had never produced the sustained speeds where eye protection was thought necessary, other than rudimentary cloth veils against insects and splashed mud. Goggles, as we know them really first start to appear in the 1890s for the burgeoning number of cyclists brought on by the introduction of the ‘Safety Bicycle’ and pneumatic tires. A trend later spurred by the nascent motorcar market. Various non-glass goggles and eye-shields appeared in the 1890s, often using mica, (a common platy crystal found in granitic rocks, but very rare and hence expensive in large usable sheets). Celluloid became common from 1900 up to WWI, at which time its explosive flammability was recognized as a handicap. The risk of splintered glass from the goggles themselves, as a perceived hazard, seems to have lessened in the mid 1900’s and more and more glass versions start to appear, as its cheapness, optical qualities and scratch resistance trumped any safety concerns.

It is well documented that the ‘Sudan Goggles’ had thick, strikingly blue lenses. Coloured glass has been available since ancient times; in fact producing ‘aqua’ or ‘crystal’ clear glass was a difficult and expensive process. Coloured glass spectacles started to be used for various therapeutic reasons from 1700 usually in blues and greens. There are images of Georgian gentlemen and Civil War troops wearing tinted glasses; these where simply tinted plain glass spectacles, ‘railway glasses’ (with folding side windows attached to the arm) or the wire mesh-framed ‘cinder goggles’ as shown here. Reference 4 goes into some of the therapeutic reasons why these were often of blue glass, however, another factor was that cobalt-blue when added to glass actually toughed it. This is the reason why old tin-ware, cups-plates etc, usually had blue rims; cobalt-blue glazes were more chip resistant, but expensive than other colours, hence just the edges were dipped in it.

Although it is well documented that these ‘cinder goggles’ were indeed issued to troops during the Sudan Campaign images of them being worn are quite rare.

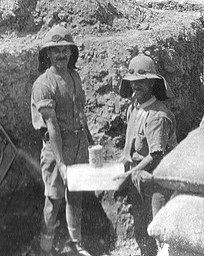

Figure 4. At left a pair of ‘Mesopotamian Goggles’ in Mesopotamia, at right a pair of ‘Sudan Goggles’. Sixteen year old Depot stock, or brought from home?

There is little evidence that goggles were routinely used in other campaigns before the First World War, but Fig. 4 may hint that they did survive and were worn, whether as old stock reissued, privately bought from ‘posh shops’ or retrieved from Granddad’s dresser drawer is unknown.

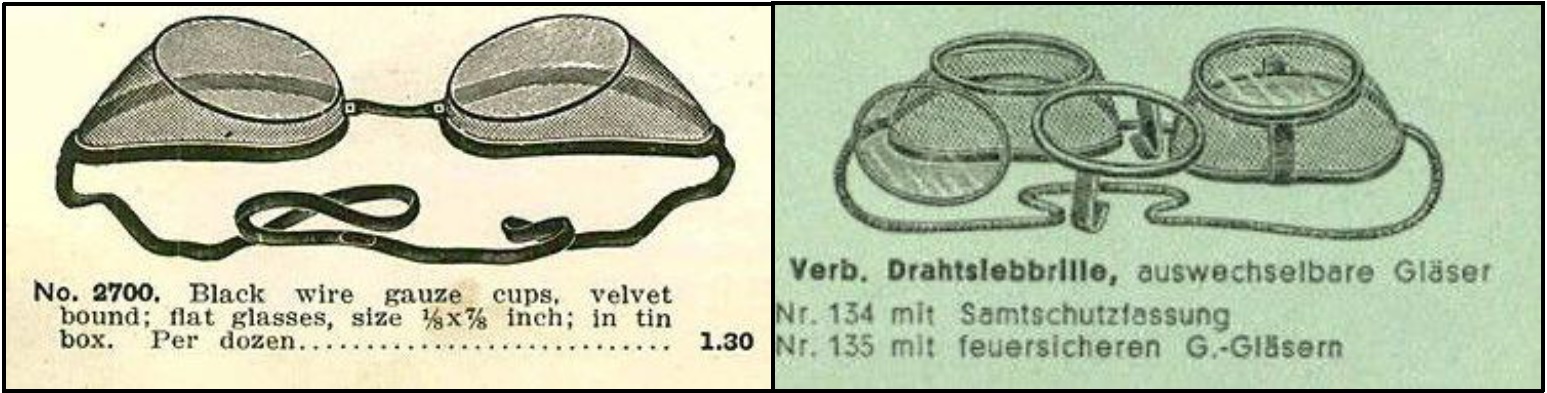

Better made versions of the ‘cinder goggles’ were in store catalogues by the end of the 1890s. These had black ‘mole skin’ velvet edging and straps. The straps are crimped to the metal mesh and then sewn into the trim, rather than threaded through an eye, the glass was typically of a black tint. The straps were significantly shorter than on goggles designed to tie around pith helmets. These should not be confused with the military and original railway type of 1850-1880’s, see fig. 3 and 5.

Figure 5. Similar styles, but these are not ‘Cinder’, ‘Civil War’ or ‘Sudan’ goggles. They are better finished and a different shape. Left, these were sold internationally to early motorists as a luxury item, compare price to Fig 3 (inflation 1880-1910 was 0.23%, 1880 8c = 1910 10c). Right, a German made pair, with detachable loops with sprung arms for lens swapping.

The ‘Mesopotamian’ goggles

At the end of 1914 the British Empire again found itself embroiled in a desert campaign, this time against the Ottoman Empire who had sided with the Central Powers. The campaign against the Ottoman Turks and their allies was to be waged on four fronts; with British forces engaging at the Dardanelles, Mesopotamia and Egypt-Palestine areas; with Russian forces engaging from the North. The Dardanelles and the Egypt-Palestine front were administered from London; the Mesopotamia front was launched by British forces in India who landed in the Persian Gulf. This may have had an important bearing on the issuing of goggles, as from at least 1907 the Indian ‘Field Service Manual’ contained regulations stipulating that when on-campaign or on-the-march ‘sun spectacles’ be issued.

Figure 7. The goggles are smooth sided, lacking the ‘cheese grater’ vents of the WWII SLM goggles. The slight curve to the glass and smooth frame with the tags for bending and securing the glass can just be discerned. Right, a pair of M&Co goggles (foreground), compared to a pair of WWII SLM’s. As well as the differing frame surface features they are larger and have a single layer of curved blue glass.

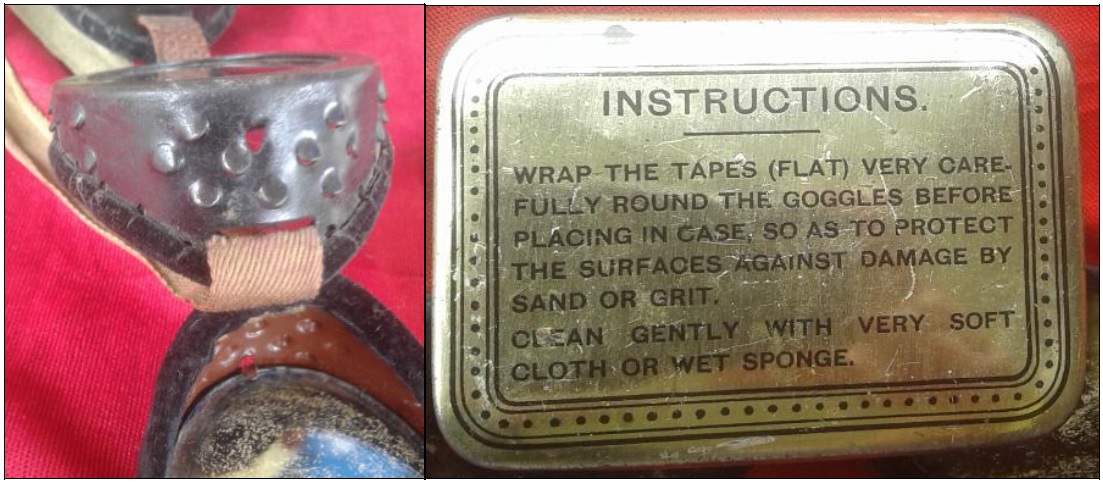

Figure 8. M&Co goggles, the ‘v’ shape tabs for holding the glass can be seen. There are spare tabs for glass replacement; being aluminum these will break off if re-bent. Circular vent holes are present at the back of the frame, which also act as stitching holes for the attachment of velvet padding. The polished aluminum frames are washed with brown lacquer to give a pleasing appearance. The tin case was identical to that in which the WWII SLM’s were issued, but M&Co goggles had a dark red lining instead of green (right). The cases were polished steel, with an instruction transfer applied and then clear lacquered over, giving a golden appearance (centre). Top right, how the case often ages.

Figure 9. Strap length. As the photograph in Fig.6. shows the straps tie around the helmet, as such there is a minimum length they can be. Here the straps for M&Co (bottom 2); an unmarked pair; a P.E.Co Ltd pair; then SLM 1940, 1941 and 1942 are compared. The ruler at bottom is 50 cm; the M&Co straps are ~51 cm (~20”) in length, so with goggles they have a tip to tip circumference of 116 cm (~46”). Easily enough to circumscribe the most voluminous pith helmet. The WWII SLM goggles have the shortest straps, between 42-46 cm.

The manufacturing mark, M&Co is not unique, with a number of companies using the monogram during the first half of the C20th (including silver smiths, watchmakers; munitions, webbing, bag and glass makers). It must be noted that the frame of a pair of goggles does not leave much space for verbose markings.

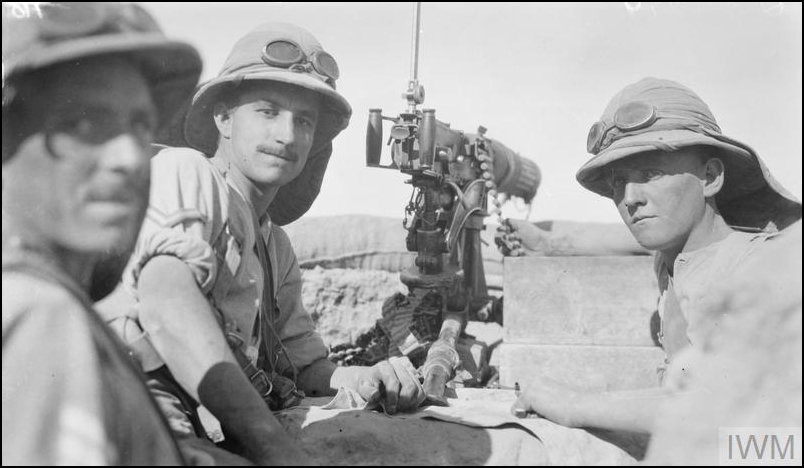

Figure 10. Top left, Slouch hat and goggles. Bot. left, A trooper takes a swim in the Tigris or Euphrates (the two potamoi of the areas name), showing confidence in the knot sercuring his M&Co(?) goggles. Right, a new aspect of war, a rail-mounted antiaircraft gun, the need for tinted lenses in such a situation is obvious.

Transition Types?

The photographs in Fig. 6 and 10, seem to show that ‘Mesopotamian goggles’ were larger and different in detail to the ‘SLM’ goggles of WWII, however, whether these ‘M&Co’ goggles were the only type used in Mesopotamia is open for debate, as the pictorial evidence is scant.

The family resemblance of M&Co and SLM goggles is obvious; the frame colour, strap material and attachment, the leather nose bridge and of course the case they were supplied in. But was the (as yet unmarked ‘SLM pattern’) used in WWI, as some would have it?

There do indeed seem to be ‘transition types’ (Fig. 11). The M&Co goggles were aluminum framed and had a single layer of blue glass; some unmarked pairs and a pair marked P.E.Co Ltd, are made of the these materials, but have the size, shape and vent pattern of WWII SLMs. Were these a transition type? Was the pattern synonymous with SLM in WWII, issued during WWI? There is probably not enough evidence for us to ever know.

Unmarked pairs, identical to WWII SLMs, being of brass and having laminated orange/brown glass, are reasonably common; are these pre-WWII versions? or war-time ones which just missed getting a maker mark and date stamp?

Subsequent to 1917 all glass goggles issued by the British military had laminated lenses. Could the small flat lensed pattern have replaced the curved lensed ‘M&Co’ pattern around that date so laminated glass could be fitted? But the earliest aluminum ones still got fitted with the same, but flat blue single layer glass as the standard M&Co’s? Again, this can only be conjecture.

Figure 11. M&Co – SLM transition types? Top left a pair marked P.E.Co Ltd, top right an unmarked pair. Unlike WWII issue SLM goggles, but like WWI M&Co goggles these two examples have frames made of aluminum and the lenses are a single layer of blue glass, the exact same tint as M&Co goggles. Bot. left, close-up showing aluminum frame and blue lens. Bot. Right, in foreground the larger M&Co goggles, made of aluminium and with a single layer of curved blue glass, as are the P.E.Co Ltd pair at centre, but with flat blue glass. At back is a standard WWII SLM pair, with heavy brass frames and laminated orange/brown lens.

Figure 12. The other ‘Mesopotamian goggles’. Turkish troops with what appear to be German made industrial goggles, deep, pressed alloy cups with square tag type vents and four distinctive large tabs for securing the lens. Very similar ones are still made today, both Britain and Russia produced identical goggles during the C20th1915-1918

‘SLM’ or ‘North African’ goggles

Figure 13. WWII SLMs, smaller than the Mesopotamian goggles. Left, being worn by a driver in N. Africa. Right, the goggles with their tin case. The wartime ones, made by ‘SLM’ have laminated glass with an orangy-brown tint and they were all made of quite heavy brass.

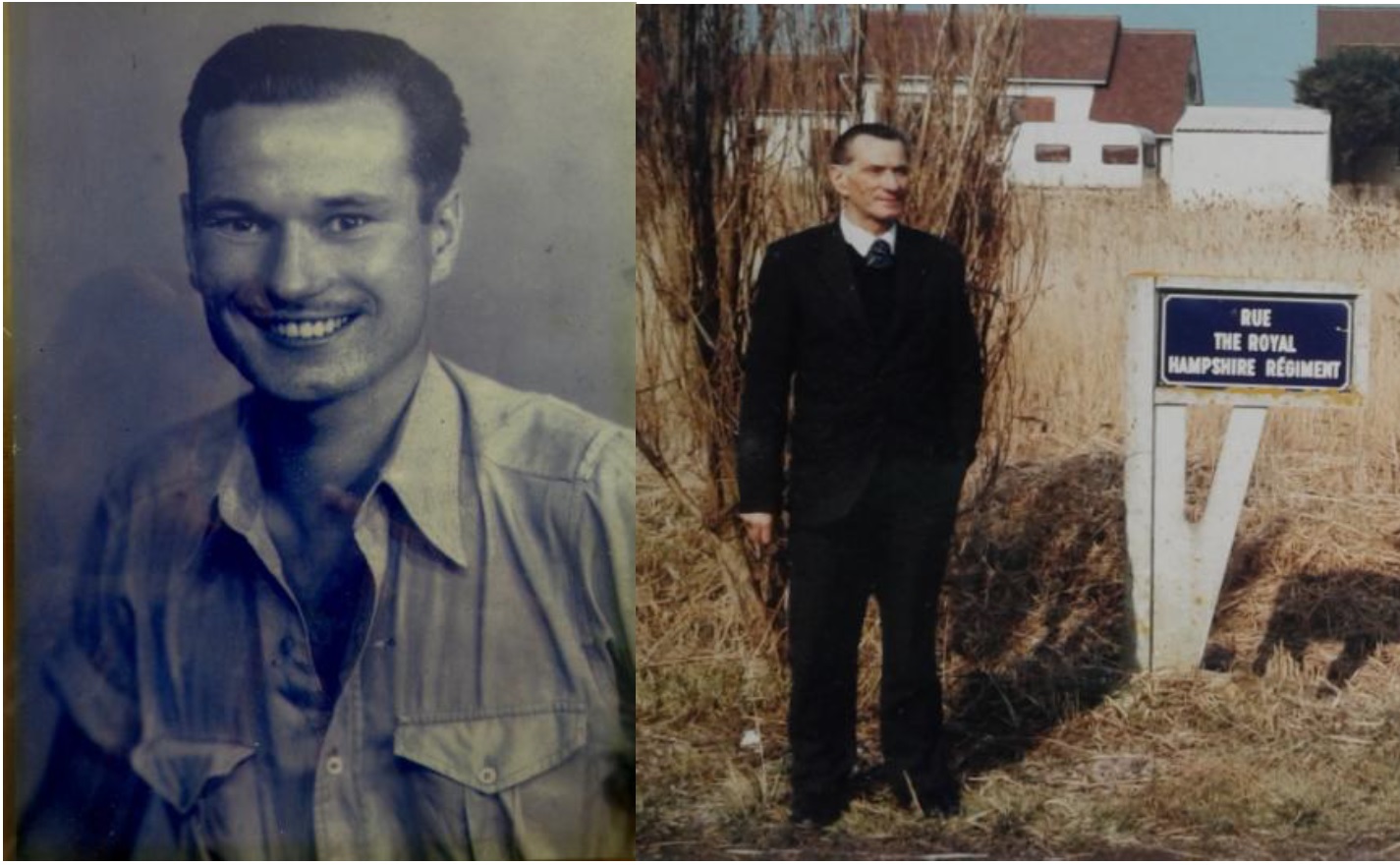

These goggles are reasonably common, they are elliptical have the makers mark on the top front of the frame of ‘S.L.M’ and a date stamp at bottom; apparently restricted to 1940, 1941 and 1942. These goggles were issued to Commonwealth troops in N. Africa in WWII. It has been said that they may have been private purchase, but my Father was issued a pair in Egypt in 1941; he was a Bren Gunner, B Company, 1st Battalion, Royal* Hampshire Regiment. Likewise reference (5) tells how Private L. Bevan of 1st Battalion, S. Wales Borderers, was issued a pair and gives their subsequent history.

Figure 14. Two of their distinguishing features, the ‘cheese grater’ vent pattern and small triangular tags for holding the lens, and the ‘Instructions’ on the tin case.

The origin of the ‘SLM’ stamp is obscure. They are not Spatial Light Modulators, as the IWM suggested. They are not from Mansfield; a web site has an ambiguous reference next to a picture of a pair, probably the location of the owner; the Mansfield Industrial museum has no record of SLM. In the right-time-frame and product scale is the American toy manufacturer SLM, but these are Commonwealth goggles and there appears to be no references to an SLM factory in the UK. Someone said they may have been an Indian company, but all roads in that direction lead to Walter Bushnell’s, James Murray & Co.,or J.G. Andon & Sons, Calcutta, all sold a type of round tie-on goggles, of the same date; but not the SLM pattern. They may have been made by the London based S. Lewis’s, whose catalogues through the 1930s include a large range of goggles, including Government contract items, perhaps SLM is ‘S. Lewis’s Manufacturing’? but this is just speculation. S. Lewis’s did make a copy of the ‘Featherweight’ pattern goggles and indeed, some ‘Featherweight’ goggles from the 1930-1940s do have SLM on the back of the nose hinge.

Figure 15. Top, three different goggle types, including leather and cloth versions of the ‘Featherweight’ pattern which became the Army General Purpose Goggle (late 1920s to early 1940s), all marked SLM. Bottom, (bot-to-top) 1940, 1941, 1942. All are made of brass. These examples show the 1940 and 1942 ones are lacquered, allowing the polished brass to show through, but the 1941 pair has opaque light brown enamel.

Although confirmed as British Army issue in North Africa and being reasonably common on vending sites, photographs of them actually being used are vanishingly rare. This may be because unlike in the Sudan and Mesopotamian Campaigns, in N. Africa other goggle types were issued to certain classes of soldier, such as tank crew, dispatch riders, transport and special-forces etc. All these groups were issued British Army General Purpose goggles (Fig. 14, top panel), based on the Triplex Featherweights of WWI. So these little SLM goggles seem to have been ‘emergency goggles’ for general troops, for use when travelling in dusty conditions, during sandstorms and possibly during gas attacks etc. The tie-on-straps make them impractical for general use, they cannot easily be slipped on and off etc. But they were small, handy and the tin made them ideal for carrying in a pocket.

From the dates inscribed on the frames, this incarnation of ‘Desert Goggles’ seem to have been introduced in 1940 and last produced in 1942, the information contained in Reference 6 may explain why they were discontinued in that year.

Acetate… ‘anti gas eye shields’. Introduced in 1937 they were designed to protect the eyes from liquid gas but were authorized for use as anti dust goggles in 1943.

So it can be imagined that the cheap acetate ‘anti gas eye shields’ were used alongside the expensive brass SLM ‘anti dust goggles’, but replaced them in 1943 when the acetate shields were authorized for use as dust goggles as well? Hence the cessation of the latter’s production in 1942.

Figure 16. ‘SLM’ goggles and the acetate ‘Anti-Gas Eyeshields’. It appears the eyeshields were carried by all troops as part of their gas protection measures, in N.Africa, the SLM goggles were also carried as ‘anti-dust goggles’. The situation was rectified in 1943 when it was authorized that the acetate eyeshields could also be used as dust shields and the relatively expensive little brass SLM’s were no longer issued.

Whether Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s unintended endorsement of the acetate eye shields as dust goggles had any influence on the British Army’s decision is unknown.

Figure 17. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, wearing the pair of British ‘Ant-Gas Eyeshields’ given him by the captured Major General Gambier-Parry in 1941, as thanks for having the latter’s cap returned. Did Rommel’s continual use of them, jog the British Administration into allowing gas-shields to be used as emergency dust goggles?

Figure 18. Sometimes SLMs and Mesopotamian goggles are confused with European ‘Alpine’ goggles, recognizable by their U shaped vents/retaining tags. These were made from 1900 to now, in Switzerland, France, Austria, Italy, Germany and latterly in the US. Sold in ski resorts and mountain shops throughout the world. German/Austrian Mountain Troops (Gebirsjager) wore a hotchpotch of goggles, including styles like these, but so did most skiers and mountaineers 1900-1960s.

With the withdrawal of the SLM goggles the era of campaign specific goggles ended. By the end of WWII the Polaroid 1021 and its derivatives; the B8 and M1944 etc, rubber framed, plastic lensed goggles ushered in a new era. By the end of the 1950s most troops world-wide were issued with a locally produced version of this style. They same basic pattern, with modern materials and styling are today’s ballistic and tactical goggles and material advances have lead to all plastic wrap-around military grade sunglasses.

The days of string or ribbons, glass and pressed metal or cloth cups, has passed.

Stanley Louis Saunders, my father. At left some time in the 1940s and right in 1993 in ‘Rue The Royal Hampshire Regiment’ in Le Hamel, Normandy, France. The first time he had been abroad since being shot in the stomach whilst advancing on the radar station above Arromanches, the morning of 7th June 1944; after landing with B Company, 1st Battalion, the Royal* Hampshire Regiment, at H+ 5 (or 7:30 am) on D-Day, the day before, when they successfully took Anselles-sur-Mer. In the 1970s he gave me his little pair of SLM goggles he was issued in Egypt in 1941. Later I actually put elastic on them and wore them whilst working on Mt. Etna in the early 1990s. I subsequently lost them and always felt a bit sad about it (Dad died in 1999). In 2014, I discovered I could buy goggles on eBay, so I did!

* My Dad always called it The ‘Royal’ Hampshire Regiment, but it wasn’t given this epithet until 1946

Steve Saunders

Rabaul, Papua New Guinea

6th February 2018

References

- http://www.militarysunhelmets.com/2012/british-army-neck-curtains

- http://www.victorianwars.com/viewtopic.php?f=16&t=8209

- http://1914-1918.invisionzone.com/forums/topic/32872-sunglasses-for-soldiers/

A very well writen and researched article about a topic I had never thought about before. Thank you for taking the time and effort into writing the article and educating, I am sure, many other collectors on this subject.

Regards

Brian

Dear Steve,

I stumbled across some goggles lately and was surprised and delighted to find such a terific writing on this subject. Had no idea before… Thank you very much!

Best regards, Robert, The Netherlands

Very detailed article – I have acquired a pair of North African SLM glasses – You say they are not uncommon but what sort of value would we be looking at? They appear in good condition although the instructions on the tin carry case, has been rubbed off.

Hi Andrew,

A pair seems to come up every month or so. Some ask £40-50, but I think £20-30 is probably a realistic price, especially if you say the case is rubbed.

Regards

Steve