The late 19th century saw the era of “Red Coats” pass as British soldiers on campaign donned khaki – which was soon to become the first true universal camouflage

Today camouflage has gone high-tech, with digicam or “digital camouflage” being the preferred pattern. This utilizes small micro-patterns as the method for effective disruption, as opposed to the large blotches of cover, which could be easier to spot with the naked eye. This is of course leaps and bounds over the earliest camouflage, which consisted of solid patterns. Among the earliest was khaki. While known for the casual pants, khaki has a long history as the first widespread military camouflage.

This is part I of a multiple part series on the origins and development of “the Original Camouflage.”

In England, irregular units, including gamekeepers adopted drab colors to hide from game and poachers, and by the Napoleonic Wars British rifle units – including the 95th Regiment of Foot (later The Rifle Brigade) – were outfitted in green jackets. This was in contrast to the scarlet uniforms of the day.

In fact, the British “red coats” dated back to the New Model Army ordinance, and were based on the traditional colors of the Yeoman of the Guard and the Yeomen Warders. While there is a common myth that red coats were favored as they didn’t show blood stains, it is likely pure fiction – notably as blood does show up on red clothing as dark, even black stain. Red had been one part of the color of the Tudor Rose, and the earliest “red coats” were worn with white trousers, while it should also be remembered that the original “Union” flag of the United Kingdom was red and white.

As the British Empire expanded it soon became apparent that “red” or scarlet tunics were not suited for the tropical climate of the Indian subcontinent. Likewise, the heavy wool uniforms were simply too warm. And yet for the better part of 70 years the British Honourable East India Company, as well as regular army troops that served in India, retained their scarlet uniforms.

As noted by colleague Stuart Bates in the book The Wolseley Helmet in Pictures: From Omdurman to El Alamein, Sir Harry Lumsden raised a Corps of Guides in 1848 for frontier service at Peshawar, near the Afghan border in what is now Pakistan. These troops wore a uniform based on their native attire rather than the scarlet tunics. This consisted of a dust colored smock and white pajamas. Originally this uniform was anything but “uniform,” but eventually the fabric was dyed with a mulberry juice giving a yellowish drab color that matched closely the local soil. It was thus named for the color of the soil, using the Persian word, “khaki” for “dust.”

“The term ‘khaki’ means ash-colored and was first used by the British by the British-indian Army Corps of Guides cavalry regiment in 1849 in order to render the troops less conspicuous in their skirmishes with tribesmen on the North-Western Frontier of India (now Pakistan),” explained British historian Nigel Thomas. “It was adopted by other British-Indian regiments during the Indian Mutiny of 1857 but then abolished, only to reappear in 1868.”

What prompted the British to abandon the color is not fully understood, but one consideration is that – as with the uniforms of the Corps of Guides – the color was not exactly consistent. In fact, over the years numerous attempts were made to formulate a dye that would provide a khaki color that was consistent and wouldn’t fade or run. These attempts failed with the uniforms varying greatly in color after only a few weeks or months of exposure to the weather.

A World War I era pattern khaki tunic. This example features insignia of the Dorset Regiment, which saw action in Mesopotamia, Gallipoli, Egypt and Palestine

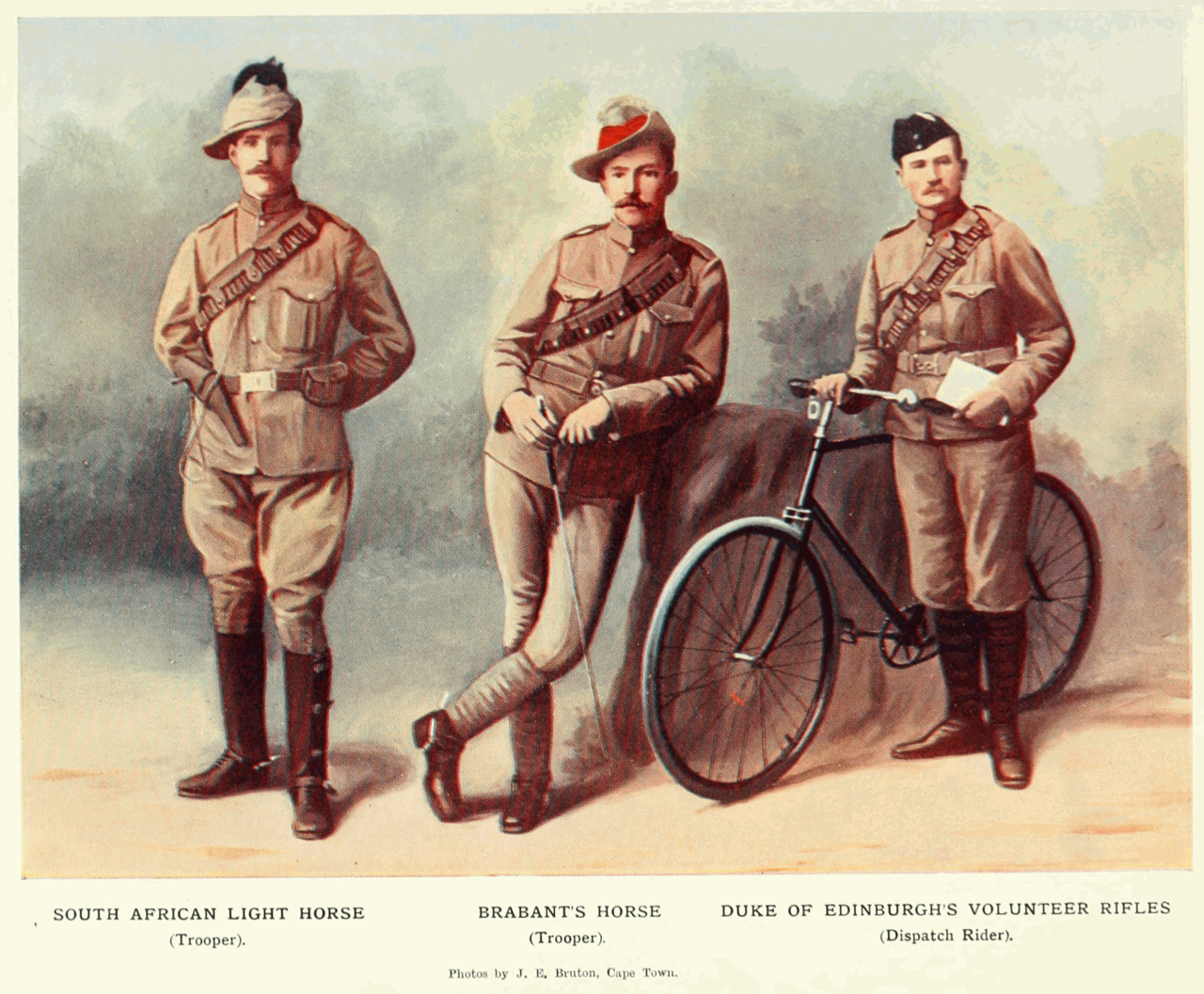

While khaki made a return in India British soldiers serving in the Zulu War (1879), in the First Anglo-Boer War (1880-1881) and the First Sudan Campaign (1882), retained their scarlet uniforms. However, by the end of the 19th century the “red coat” was duly replaced by khaki.

It should also be noted that it was commonplace for troops to stain their white uniforms and helmets with any appropriate substance in order to break up the white and therefore provide some camouflage. A variety of materials, including mud, tea, coffee, tobacco juice and even curry powder were used.

The problem was “solved” when a fast-dye was patented, which produced a consistent yellowish-brown color that would be retained over a prolonged period.

“During this period it was a grayish color drill fabric but when the British Army adopted it for the Second Boer War of 1899-1902,” explained Thomas. “It had become a light yellowish brown, the color through the two World Wars until the present day for tropical uniforms.”

British M37 pattern “bush jacket” and trousers – these are not cotton KD, but rather heavyweight corduroy. This pattern uniform was used in North Africa and the Middle East during World War II

However, the color did evolve as well, and became darker brown from the tan-colored dust. In 1924 the new shade was formerly introduced and it was slightly greener than the one it replaced.

“The British Army adopted khaki serge for its service uniform in 1902 and for the battledress field uniform 1939-1962,” says Thomas. “Khaki serge was a much heavier fabric than khaki drill and was intended for fighting in winter in north-west Europe. It was a darker greenish brown, the amount of green depending on regimental tradition.

Indian-made M37 Battledress. This pattern is based on the version used in Europe, but in the lighter KD (khaki drill cloth), and was used primarily in Burma and Iraq at the beginning of World War II

During World War II the British had found that khaki drill was actually impractical in the jungles of Burma, and actually dyed green the uniforms while exploring options for more suitable jungle uniforms. The result was a Jungle Green (JG), which had a significant flaw, in that it darkened quickly as soldiers sweated in the cotton uniforms. The French experienced a similar flaw when they too replaced the khaki with American colored Olive Drab (OD) for use in Indochina in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The JG was replaced by a similar looking OG (Olive Green), which was used in Europe as well as the Fast East including Malaysia in the 1950s and 1960s.

The post-World War OG (Olive Green) is based on the late World War II JG, which was used in the Far East. This pattern tropical jacket was used in Malaysia in the 1950s

With this khaki’s use by the British began to diminish, but the story of the “dust colored” camouflage was far from complete.

MTP indirectly is the return of Khaki!