The name Frederick Charles Denison may not be as well known as that of Garnet Wolseley, but Denison played an important role in the Sudan Campaign when he commanded the Canadian Voyageurs on the Nile. Denison distinguished himself during the war, and was given prominent mention in dispatches but he also received multiple honors and awards.

Had Denison not taken part in the ill-fated campaign, he still would have left his mark as a militia officer, lawyer, author, businessman and politician. Born to the wealthy and influential Denison family, he was drawn to military service after his older brother Captain George Taylor Denison III became a militia officer.

As a student he gained a 2nd class certificate, which qualified him to command an infantry company, from the School of Military Instruction run by the British army in Toronto. He later joined the 1st Volunteer Militia Troop of Cavalry of York County, which in April 1866 became the Governor General’s Body Guard under George Denison’s command. Frederick Denison served with the unit in the Fenian Crisis of 1866 and it was likely around that time that he met then Colonel Garnet Joseph Wolseley.

When George Denison resigned his post following a dispute with Sir George-Étienne Cartier, who served as minister of militia and defence, Frederick Denison assumed command of the Body Guard and was promoted to the rank of captain. After serving as an alderman from St. Stephens ward on the Toronto City Council from 1878 to 1883, Denison traveled to England with his wife where the couple was presented by Wolseley at court, but also given an opportunity to see the British Army at training.

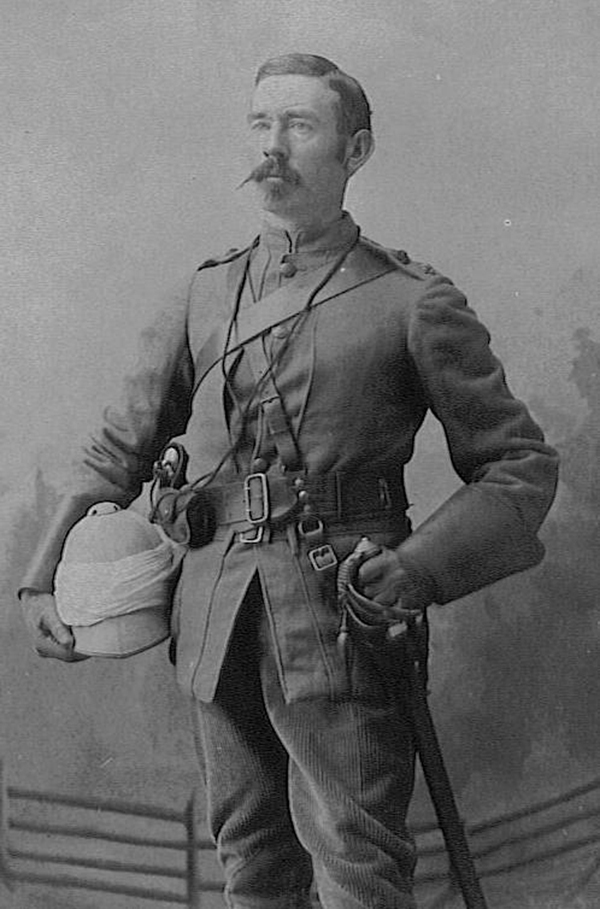

Major Frederick Denison in the uniform he wore during the Nile Expedition. It isn’t clear if this is the same helmet with puggaree added, but it appears to be of the same style.

The Nile Campaign

In 1884, after much procrastination the British government decided to act and send an expedition to the Sudan to counter the fundamentalist insurrection led by the Mahdi and to relieve the besieged city of Khartoum, which was under the command of Major-General Charles George “Chinese” Gordon.

The expedition to the Sudan was led by Lord Wolseley, who concluded that the Nile would be crucial to moving men and material to the Sudan. Denison, who had taken part in the Canadian Red River expedition, seemed like just the right man for the job and the then 37-year-old lawyer and amateur soldier was called to act.

After receiving the brevet rank of lieutenant colonel, Denison arrived in Egypt to find that the relief column was struggling to upriver. Denison helped whip the Canadian Voyageurs into shape and step up the progress. In early February 1885 the Mahdi resistance increased – in part because unknown to the relief column Khartoum had fallen and Gordon killed weeks earlier – but the British-led column pressed on.

Denison came under fire for the first time in his military career, and for nine days the army was dependent on his Voyageurs to transport supplies as they battled the fanatical Sudanese warriors. After being hospitalized for some six weeks in Cairo with enteric fever, he finally arrived in London in May and found himself a minor hero for his actions on the Nile. He was made a companion of the Order of St Michael and St George. He returned to politics, but died of stomach cancer just 10 years later.

Today, Frederick Denison is best known for commanding Canadians in their first military venture overseas as part of an imperial force.

A British Foreign Service Helmet that was worn by Major Denison during the Nile Expedition. The helmet was likely whitened for use in Canada as the Canadian militia adopted the Universal Pattern Helmet in 1886.

A Private Purchase Helmet

At the time of the Nile Expedition it should be noted the Canadian militia worn WORE a Home Service Helmet, which was patterned after the British version – a dark blue (in some cases almost black looking) helmet that featured a unit plate on the front with a spike and base on the helmet’s dome. This helmet was introduced to Infantry, Artillery and other arms in 1876, but not Cavalry. There were only two types of Cavalry in Canada, Hussars and Dragoons. Hussars wore the busby and the Dragoons wore the Albert pattern helmet. The Governor General’s Body Guard normal headdress would have been a silver dragoon-style cavalry helmet with tall white plume.

In 1884, George Denison III once again took command of the Governor General’s Body Guard in Fredrick’s absence. The Body Guard were tasked the following spring of 1885 to assist in quelling a native rebellion in Western Canada. While on Campaign the Canadian field force found the open plains to be unbearable with the hot sun beating down on the troops. The Body Guard soldiers wore their pill box caps in the field, and left their heavy steel helmets in camp. It was not until the end of the campaign that there was a late delivery of much needed new white “universal pattern helmets” from England to the contingent for general issue.

The Body Guard returned to Toronto that summer wearing these sun helmets on their victory parade. It was not until 1886 that the Canadian military officially adopted this white helmet pattern to replace most all headdress, including the home service helmet, to be worn at home in garrison in Canada and in the field and abroad. The 1886 issue was manufactured in a factory in Montreal, Canada. As Denison’s extraordinary adventure occurred prior to the issue of this helmet to the Canadian Army in 1885 he would have no such helmet before leaving Toronto.

Because these white helmets were not in circulation in Canada in 1884 and Khaki uniforms were not on issue to Canadian troops at home, as commander of the Canadian Voyageurs he would have had to acquire a complete Khaki wardrobe and helmet on arrival in England. He needed a full uniform appropriate for overseas service in the hot African climate dressed as a British serving Officer. This would have been the British styled Foreign Service Helmet – or pith/sun helmet – which was worn by most of the British troops in the campaign. As Denison had regularly traveled to London it would not have been unusual for him to have contacts with the military outfitters.

The interior shows a high quality but certainly well used sun helmet

This would have been the British styled Foreign Service Helmet – or pith/sun helmet – which was worn by most of the British troops in the campaign. As Denison had regularly traveled to London it would not have been unusual for him to have contacts with the military outfitters.

His helmet came from one of the many hatters operating at the time, Hill Brothers of Old Bond Street London. Why he opted for this maker over the more popular Hawkes or Ellwood isn’t apparently clear, but one factor may have been cost while another could be availability as there was no doubt a “rush” of sorts to outfit the men heading off to Africa, not to mention the usual rotation to other parts of the British Empire.

The original helmet tin from Hill Brothers of Old Bond Street in London.

The helmet tin denotes that Major Denison was commander of the Canadian Contingent for the Nile Expedition. This suggest the helmet and tin were purchased in London prior to the expedition.

This particular helmet does appear to be of the type used in the ill-fated campaign. The wear to the interior is also consistent with what we would expect to see in a helmet used “on campaign” in the harsh weather of the Upper Nile in the heat of the Sudan.

While the author obtained this helmet, it has since been offered to the Governor General’s Horse Guard’s Cavalry and Historical Society, where it will be on display with Denison’s medals and other personal items and hopefully will honor the legacy of the man who sought adventure as an officer and a gentleman.

Peter Suciu

September 2020