Since posting last month about “The Forgotten American Experimental Helmet,” more information on this particular pattern has come to light. Apparently the helmet isn’t really so forgotten as it does appear in several reports and even some news accounts.

Even more interesting is the fact that a collector has come forward not only with some additional details but some photos of the actual helmet! Collector Marc Giles currently owns what is for now the only known surviving example of this helmet.

Giles noted:

“The U.S. rigid fibre [sic] sun helmet was one of the only items of headgear that was not researched or designed by the military establishment but simply adopted for use from a commercial design manufactured by the Hawley Products Co., St. Charles, Illinois. In 1942 the standard U.S. sun helmet came under scrutiny by members of the Army organized to review the effectiveness of equipment currently in use for desert and jungle warfare. This group determined the current standard sun helmet was not adequate. Specific objectives seem to have been to make a new helmet that was light weight, provided adequate air circulation around the head and would afford protection to the face and neck from the sun and reflect radiation. The suspension was designed to be removable to allow for telescope stacking of the shell during shipment.

“This experimental helmet was manufactured by the Hawley Products Co., St. Charles, Illinois. It seems to have undergone trails in 1943 along with other variants. This version was tested again in the deserts of Arizona in 1947, along with other equipment intended for use in desert warfare, during Task Force Furnace.”

Giles also remarked that the helmet is similar in design to the American “Liberty Bell” helmet, which was introduced at the end of World War I. That experimental steel helmet was one of several patterns considered by the U.S. military as a replacement for the British MkI, which was produced under license as the Model 1917 steel helmet. The Liberty Bell was designed by Major James E. McNary and submitted to the American Helmet Committee. While it was initially accepted it was disliked by the troops and the helmet was officially abandoned as a replacement helmet in 1920.

Two points are worth noting – they being that while the troops may have disliked it it was probably only a minor issue and the bigger point is that the war had ended, so introducing a helmet to an army that was seeing troop reduction was probably not necessary. The second point is more significant; according to Giles it was Dr. Bashford Dean, who oversaw the program to develop an experimental steel helmet, noted in an interview in the 1920s that the Liberty Bell “was an almost perfect defense against sunburn.”

It isn’t hard to see the Liberty Bell in the experimental helmet that was used during the Task Force Furnace testing by the Desert Warfare Board.

Compare the experimental sun helmet to the Liberty Bell and the design is similar (Collection of Marc Giles)

The helmet still doesn’t appear to have an official moniker – it is simply described as “the helmet” in various news reports and articles – including the Popular Mechanics magazine article on Task Force Furnace. The helmet is mentioned in the Quartermaster Equipment for Special Forces (Q.M.C. Historical Studies, No. 5 – Pages 92-92), which noted:

“The helmet liner [Author’s note: likely the M1 steel helmet liner], in standard type and in experimental variations designed for extra coolness, formed part of the first shipment of Quartermaster items to the Desert Warfare Board. Use of the standard liner in the desert showed it to be a generally satisfactory form of headgear, but some additional cooling and ventilation were desirable. A thin sheet of aluminum foil, placed inside the liner at the top, served to reflect some heat. A coating of infra-red reflecting, paint made some reduction in temperature. Holes punched in the shell of the liner offered an obvious means of extra ventilation, but took away its waterproof qualities. Such ventilating holes were also, of course, shut off when the steel helmet was worn over the liner, as under combat conditions. Another devise which received some attention was an extra brim for attachment to the liner, to furnish shade for the face and neck.

“Experimentation along these various lines continued in the office. The use of aluminum foil was discouraged by the Surgeon General’s Office, on the ground that bits of aluminum would be carried into head wounds and complicate them. With the occupation of most of North Africa by the Allied forces, cork, which had been a scare material, became available for design and attention was directed to it as a means of insulation for the helmet liner. There was an improvement in the suspension for the helmet liner at this time, however, which provided better ventilation. The Desert Warfare Board approved the liner as issue, except for the fact that it did not give adequate protection to the back of the neck. There was further experimentation with detachable brims to meet this situation.

“Along with efforts to improve the standard helmet liner for use in hot climates, the tropical helmet, traditional badge of the white man in the low latitudes, for the first time came under scientific study. A revised specification for the tropical helmet, which was already being issued for garrison use in hot countries, appeared in June 1941 and members of the Special Forces Section working on desert and jungle problems sharply criticized it. They considered it definitely inadequate. It was too small for good ventilation and too thin for full protection from the direct rays of the sun. The problem of designing a tropical helmet on scientific principles was taken up. There was experiment with various designs, involving both alternative shapes and alternative materials, in cooperation with the Bureau of Standards and other agencies. The objectives were to get the maximum air flow, consistent with efficiency, between the head and the helmet, and to secure the most effective material, or combination of materials to reflect radiation.”

The Quartermaster Equipment for Special Forces report went on to note that the project to study how the M1 helmet liner could be used as a sun helmet was discontinued by direction of Headquarters, Service of Supply. The report then added:

“But consideration of the terrific heat likely to be encountered in the summer in such areas as the Red Sea coast and the Persian Gulf brought a revival of the study. The Office of the Surgeon General gave its opinion that there were a number of areas where the protection afforded by the helmet liner would be insufficient and where, under non-combat conditions, a tropical helmet should be used. Work was pushed ahead once more on a helmet to meet this need. In the spring of 1943 a helmet designed on really scientific principles was ready for testing. Samples in several different shell arrangements were prepared by the Hawley Products Company of St. Charles, Illinois. The shape had been determined by laboratory research to allow maximum air flow. The shells, of impregnated, waterproof fiber, were made up in both single and double thickness and, since the Surgeon General’s Office had withdrawn its objection to the use of aluminum, both with and without layers of aluminum foil. The suspension was designed to hold the helmet firmly on the head, but was removable so that the helmet could be stacked compactly for shipping in quantity.”

The liner does appear quite different from the standard pressed fiber helmet liner and is clearly based on the liner developed for the M1 steel helmet’s liner system (Collection of Marc Giles)

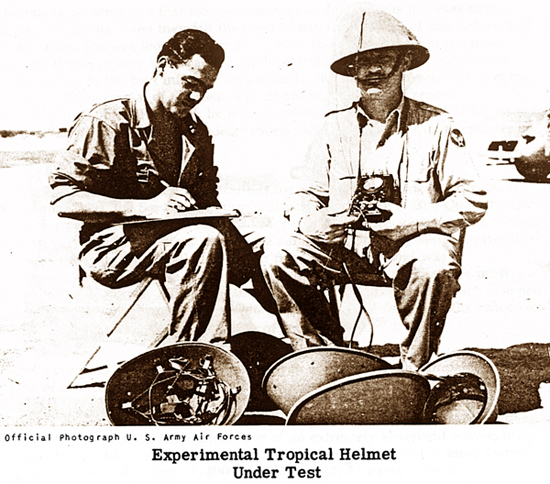

Giles further noted that he is convinced that the current standard pressed fiber sun helmet was one of the ‘other’ body styles tested at this time. His rationale, which this reporter agrees with is, is that if for no other reason, the current sun helmet would have been used as a baseline or control for measuring improvements. The other evidence is that in the photo of the testing there is a pressed fiber helmet.

Note that the standard pressed fiber helmet appears in the right of the photo – suggesting it was tested along the experimental helmet

Moreover, Giles suggested that perhaps the other “mystery” experimental pressed fiber helmet may have been used in this testing. The International Hat Company may have offered its own solution to the problem by adding greater ventilation to the side of the helmet. This author should note that since purchasing the helmet with the extra ventilation two other examples have surfaced – suggesting a cache of these may have been recently discovered.

This helmet was produced by the International Hat Company and offers “improved ventilation.” It is unclear if these were designed for testing during Task Force Furnace (Collection of the Author)

All this certainly sheds some new light on the experimental helmet that does appear to have been produced in small numbers. The example in Giles collection appears to be unissued and it may very well be the only surviving example.

This newspaper article from 1947 describes “cool-looking hats designed to catch a ‘stream flow of air, suck it in and then send a cooling stream down the back of the neck.” It isn’t clear how this was accomplished exactly!

I am a collector of military helmets from all countries. Today, I saw this article and thought that I should respond. I have a mint condition tropical helmet like the one in your article. I obtained the helmet over twenty years ago from an army veteran, who had kept it in a trunk untouched since its manufacture. I have over one thousand helmets in my collection and I am very interested in experimental helmets. (I also have U.S. experimental helmet number 7)