Discussed here are two types of ‘Flying Sun Helmet’; first, a type of cork crash helmet, which used Colonial Helmet construction methods, but whose primary function was protection from impacts rather than the sun, and secondly a true hybrid sun helmet, whose inception was to protect against the sun whilst flying in exposed cockpits in areas where such hats were traditionally used.

Discussed here are two types of ‘Flying Sun Helmet’; first, a type of cork crash helmet, which used Colonial Helmet construction methods, but whose primary function was protection from impacts rather than the sun, and secondly a true hybrid sun helmet, whose inception was to protect against the sun whilst flying in exposed cockpits in areas where such hats were traditionally used.

Although the early 1920s to early 1940s ‘Cork Helmet-Aviation’ (a.k.a., ‘RAF Type-A Flying helmet’ or ‘East of Malta Helmet’) is the best known aviator’s sun helmet, with various examples having been covered on this site by Peter Suciu and Roland Gruschka (Refs. 1 & 2), some earlier flying helmets also owe their origins or construction methods to military sun helmets.

Earlier ‘Flying Sun Helmets’, the background

Early aircraft were basically kites with an engine; the pilot’s seat was an afterthought and was often no more than a short wooden plank bolted on top of a simple frame. Pilots regularly fell or were thrown off; even at heights of only a few meters and just tens of mph serious injuries were extremely common and often fatal. Around 1910-12 the alarming death rates among unregulated aviators lead to a drive to improve safety (e.g. The Literary Digest, 1912, Ref.3). The Roold Helmet had been devised in 1910, but other manufactures also met the challenge by producing other crash helmet styles, bucket seats, harnesses, undercarriage brakes and other novel equipment. Around the same time many nations introduced regulations, with mandatory pilot training and certification.

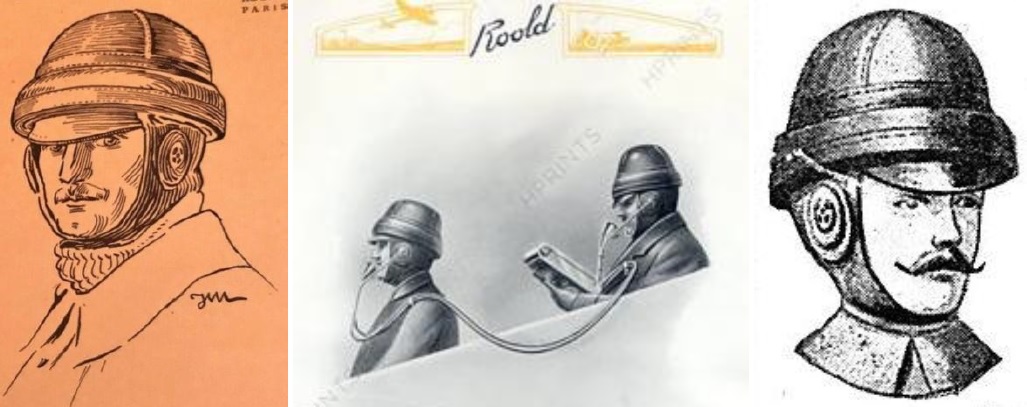

Figure. 1. Early attempts at aviation safety helmets; some best described as ‘contraptions’. Left, a 1910 British ‘Gamages’ design. Center, the 1912 ‘Warren’ helmet, consisting of sprung steel leaves in the crown and horse hair padding (the term ‘Warren’ helmet is sometimes mistakenly applied to British copies of the Roold). Right, A 1913 Dunhill’s advertisement, including the Gamages (top right) and Roold (bot. left) designs, and at bot. right a German compressed fiber or leather helmet with simple stuffed sausage buffers, which became very popular in Germany in the latter years of WWI. The Roold type helmet became the most popular safety/crash helmet internationally in the pre-war years probably due to its relatively neat appearance and well padded chamber. (Ref. 4, Aviation Ancestry.co.uk))

French Colonial Helmets take to the Air

During the late 1900s France was the leader in most things aviation, as witnessed by words such as ‘aileron’, ‘fuselage’, ‘pitot’ etc. In the US the Wright Brothers’ fierce enforcement of their patents had stifled developments; elsewhere things were half hearted and usually pursued by a few private individuals. This meant that the most up-to-date aircraft, equipment and aviation clothing tended to be French in the fledgling ‘Blériot’ years ~1909 to WWI.

In 1910 ‘Roold’, a Paris department store, commissioned the inventor M. F. Gouttes’ design of a moderately complex aviation crash helmet. This led to the famous pre-and early WWI Roold Helmet – ‘Casque pour Aviateurs ROOLD’, or ‘Casque d’Aviateur’. It was adopted by the French military in 1911 and later by several other nations; it was also copied by many companies in several countries.

That the Roold Helmet was indeed based on colonial sun helmets is alluded to in its description in a Roold 1911 information and advertising pamphlet; – ‘The Roold helmet, which is similar in shape to that of a colonial helmet, consists of two overlapping cork and gutta-percha caps, leaving a free space between them’. (N.B. ‘gutta-percha’ is resinous latex derived from a tree, but not the rubber tree). Also the ear holes used the four spoked collets normally found in sun helmet vents, indicating they came from the same factories.

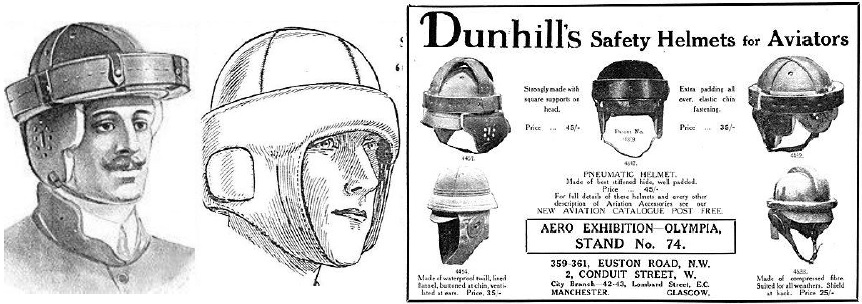

Figure 3. Roold’s professed ‘Colonial Helmet’ style, double cork shell construction, with a chamber between them. The chamber was to house padding; the original design called for steel wool, (la paille de fer – patent principle No. 438.599), but later horse hair and other materials were used. The whole is covered with a special waterproof and washable painted cloth supplied by the company Loreid.

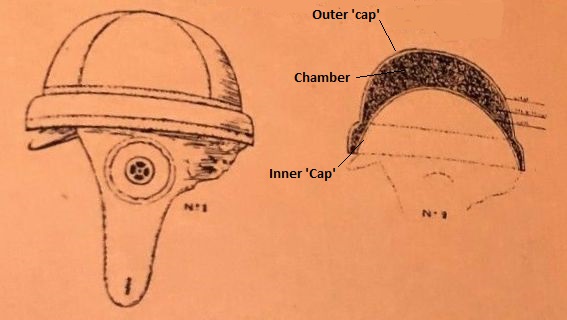

Figure 5. Examples of Roold Helmets. Top Left, typical example. Top center, example without a peak. Note the ear holes contain four spoked collets as in the vents of the M1886 Casque Colonial, without the threaded centre. Top right, an example with the tapes missing which usually cover the slit-pin heads which held the layers and liner together. Note the chin strap is joined by either buckles or double buttons. Bottom Left, example with six eyelets in the ear flap. Bottom right, the three layer construction; inner layer is the inner cork ‘cap’ with the liner and headband (a typical colonial helmet plain leather strip sewn to and folded upwards over a compressed fiber backing ring); the thick central layer is the ‘plug’ to the chamber, holding in the padding; the outer layer is the rim of the bell shaped outer cork ‘cap’.

Figure 6. British copies of the Roold Helmet. Example at center and right was made by Hobson & Sons. These appear to be a close copy of the Roold helmet. Notice the ear holes utilize the eight spoked vent pieces usually seen at the top of British sun helmets. Note, these helmets are sometimes mistakenly called ‘Warren Helmets’, but those were a specific design with a much more cushioned appearance (see fig. 1).

Figure 7. The German version of the Roold type, first produced in 1912. Similar concept to the Roold, but the cork is leather covered and the chamber is left unsealed and contains a rubber frame. The soft frame was centered and held between the two caps by threads sewn to a button on top of the dome, this was the type’s main external distinguishing feature. The sponge rubber buffer contained air bubbles, leading to it being called a ‘Pneumatic Flying Helmet’. It had a standard German style fingered headband/liner with drawstring. Bottom right, A period photo of Germany’s two main types of crash helmet, left the cork ‘Roold’ type and right, the leather or fiber type. The ‘Roold’ type was popular with German aviators early in WWI, but the lack of access to cork and rubber meant the fiber or leather crash helmet with external stuffed buffers (right and Fig. 1) had become the standard German crash helmet by mid-war.

The End of the Cork Aviation Safety or Crash Helmet.

During WWI as pilots receded into more enveloping cockpits; snuggly strapped into bucket seats behind increasingly efficient windscreens the need for crash helmets became less obvious, as simply falling out, or off the aircraft, and low speed crashes became rarer. Also with the advent of fighter aircraft the ability to swivel ones head and have good peripheral vision became important. As such flying helmets became close fitting skull caps, to protect from wind, rain, engine lubricants, fuel and flame; and were increasingly seen as simply an attachment point for communication gear, and latterly oxygen masks. Flying Crash Helmets became rare after ~1918 and soft helmets were the norm until the end of WWII, with the exception of special armoured ‘flack helmets’ for strategic bomber crews. It was only with the advent of the Jet Age, with the need for ejector seats, that composite full face crash helmets once more became the standard in military aircraft.

The British Empire’s 1920s to Early 1940s ‘Cork Helmet – Aviation’. These are true ‘Flying Sun Helmets’ and are probably what come to mind when the term is mentioned.

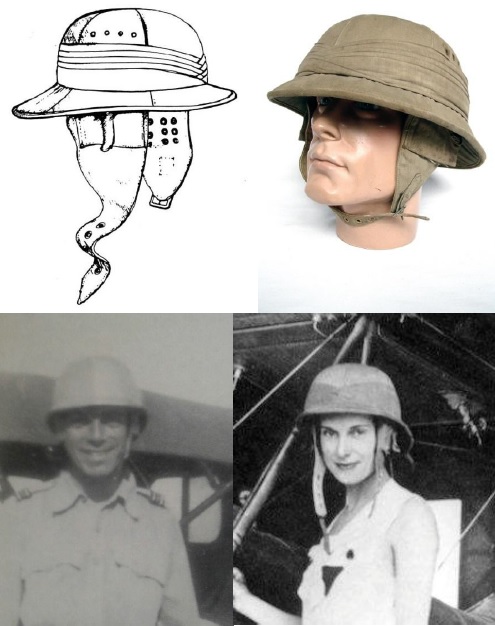

Figure 8. The ‘Cork Helmet-Aviation’ or RAF ‘Type-A Flying Helmet’. In 1922 these were given RAF stores reference number 22c/13, but later (~1940) it was renumbered and occupied the stores range 22c/274 to 22c/284 denoting 10 different sizes from 6 ½” to 7 ¾”. All those seen by the author with an Air Ministry acceptance stamp seem to be fitted with ‘Comfortilet’ liners, a registered patent of Charles Owen & Co., London, hence they were probably the manufactures of these official RAF issued helmets.

The Cork Helmet-Aviation, were a simple early 1920s adaption of the compact ‘polo’ type sun helmets, which had come into use in the 1900s (Ref. 5 & 6). Usually a button-less version was taken and simple canvas ear flaps with chamois inner lining and integral buckle and strap were attached between a standard sun helmet’s liner and shell; the laced in ‘Comfortilet’ liner made this a simple but secure method of attachment. The ear flaps had rows of brass eyelets coinciding with the ear, usually but not always, covered with a canvas pouch for gosport tubes or ear phone retention. Official Air Ministry (RAF) acceptance stamps are most commonly (exclusively?) found in helmets made by Charles Owen & Co, London, with the prominently marked ‘Comfortilet’ patented liner. Other UK manufacturers of the same button-less ‘polo’ helmet were Vero & Everitt Ltd and Failsworth Hats Ltd, although usually with felt/cork laminated shells; it is not known if these were ever used as Type-A flying helmets.

Figure 9. Other versions of the ‘Cork Helmet – Aviation’. Left, a South African made example with that country’s signature 1930s – WWII polo helmet, with top button. This helmet was made domestically by SAPHI. These helmets were adopted in 1934 by all branches of the SA military and civil authorities. It appears that the SAAF converted them to flying helmets in the same way the Charles Owen & Co (Comfortilet) model was by the RAF in Britain. The middle image shows a ‘Bombay Bowler’ (see Ref. 1 & 7) made in the UK by J. Compton Sons and Webb Ltd. It is marked 80 Squadron and appears to have been converted for flying by adding lightweight leather earflaps with a simple elastic strap and hook; the original leather chinstrap is still attached and looped over the front brim. Left, another Bombay Bowler with RAF flash and military general purpose ear phones (DLR No.2) in rather large Type A style earflaps; but the real pith shell is a commercially made Indian item, by Wahee & Wahel, Fyzabad Cantt, Uttar Pradesh.

It seems the term ‘Cork Helmet-Aviation’ can be said to contain three distinct groups: –

- The official RAF issued item, which appear to have been produced by Charles Owen & Co, with their ‘Comfortilet’ liner. This seems to be the only one which can carry the title RAF ‘Type A Flying Helmet’ description and the 22c/13 (22c/274-22c/284) stores numbers.

- Officially issued commonwealth produced standard items, such as the SAAF one shown above, which will of course not have the RAF Type letter or stores reference numbers, (more research is needed on these types).

- Conversions of locally procured sun helmets. These can be any style of compact sun helmet that has been converted to a flying helmet by the installation of earflaps and strap. These may be of civilian or military origin. It is not known if the standard ear flaps were available from stores, or whether Air Ministry Orders contained instructions and dimensions for their local production; such instructions certainly did exist in similar cases with the 1936 AMO 207 ‘Receivers, Telephone-Instructions for fitting to Caps, Flying (1930 Pattern), (Stores Ref. 22c/51)’, which gave the pattern and instructions for local production and fitting of flaps to existing helmets. That the converted types were fitted with regulation type flaps and also simple locally made flaps can be seen in Fig. 9. Examples exist constructed of pith and examples in other commonly encountered materials may also occur, which makes the ‘Cork’ part of the group’s description not quite accurate.

During the period when the ‘Cork Helmet-Aviation’ was used, open cockpit flying meant that in the tropics the pilot’s head was exposed to the sun for long periods of time. As well as the purely practical need for head protection, culture would have played a major role in their adoption. The ‘right kind’ of sun helmet was considered a mandatory item in the tropics, with the idea of going out ‘uncovered’ by one being almost unthinkable (Ref. 7). The wearing of sun helmets in the tropics by all European members of the Empire was therefore culturally mandated; so it is no surprise that they were an obvious, even inevitable choice for use by open cockpit aviators in those areas, just like it was for open top motor vehicle occupants and those on horseback.

In the early years of WWII these helmets became obsolete, due mainly to the disappearance of open cockpit aircraft; ones normal sun helmet could be confidently removed when entering the enclosed aircraft, without breaking protocol! Also a lightweight cotton canvas copy of the standard leather C-Type helmet was produced, the D-Type, for use in tropical areas.

In canopied cockpits sun protection for the eyes and face did continued in the form of visored ‘crush caps’ and various ‘baseball’ style hats.

Steve Saunders

July 2019

Rabaul, PNG

References:

- http://www.militarysunhelmets.com/2012/the-helmet-cork-aviation-22c13-type-a-flying-helmet

- http://www.militarysunhelmets.com/2012/the-fly-girls-of-the-british-empire

- http://www.oldmagazinearticles.com/article-summary/1912_aviation_invention_article#XSgEQ-szaUk

- http://www.aviationancestory.co.uk

- http://www.militarysunhelmets.com/category/polo-helmet

- http://www.militarysunhelmets.com/2012/the-polo-helmet-connection

- http://www.militarysunhelmets.com/2014/the-bombay-bowler

- Francis A. de Caro, Rosan Augusta Jordan. 1984. Chapter 7, ‘The Wrong Topi: Personal Narratives, Ritual, and the Sun Helmet as a Symbol’. Indiana University Press.