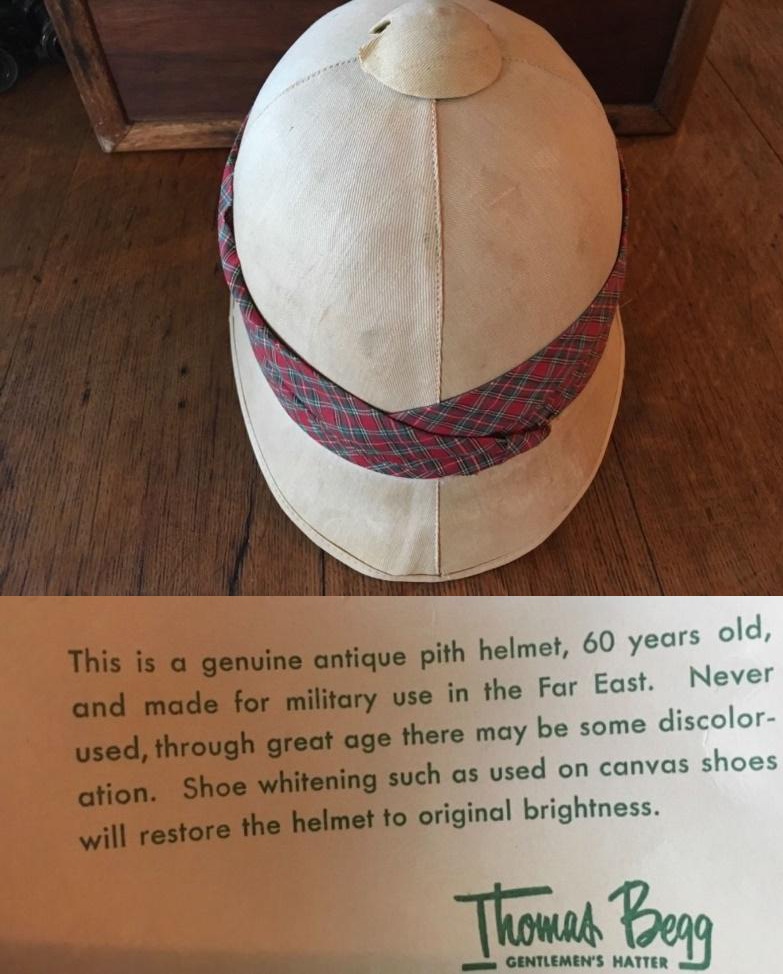

Figure 1. A ‘Thomas Begg Inc.’ refurbished M1887 helmet, with its 1960s explanatory card, the helmet is now at least 110 years old and possibly 131. A number of these re-worked helmets are thought to have been retailed by the company in the 1960s, but the cards have rarely survived

As described in Peter Suciu’s and Stuart Bates’ excellent ‘Military Sun Helmets of the World’1 and in several articles on this site, the United States Army initiated development of a lightweight cloth covered cork sun helmet, for use with a proposed new summer uniform in the 1870s. Being specifically meant for a practical summer field uniform the design was to be fundamentally different from the brass ornament bedecked, black felt helmet then worn by the Army. The existing Army helmet had merits on the parade ground, but proved impractical on maneuvers and on campaign.

The first approved summer cork helmet was the ‘M1880’, these appear to have been produced with both khaki and white cotton twill skins. Six thousand were produced, but it appears not many of these were actually issued, the reason is unknown, but it is clear that an intent to issue sun helmets continued over the next few years. The introduction of a new uniform in 1887 included a redesigned summer helmet, the ‘M1887’ model, with a wider rear brim and steeper sloping front visor. Initially it was produced in white, but in 1889, in the interests of camouflage (and stain management?) the same design started to be produced in khaki cloth, this simple colour variation earned the designation ‘M1889’.

Figure 2. The three basic C19th US Army military sun helmets. Left, a Khaki colored M1880, with wide flat brim, middle, the M1887, with steeper front and side brim, and extended rear to shade the neck, it was produced in white cotton twill. Right, the M1889, identical to the M1887 but in khaki cotton twill.

As their primary purpose was as an everyday practical lightweight sun helmet for all troops, they were not authorized for use with dress uniforms until 1904. For the same reason the addition of spikes, badges and other accoutrements was always discouraged and officially forbidden in 1887. This may have been so the relatively fragile cork structure was not compromised by the resulting piercing and added weight. There is, however photographic evidence and reliably provenanced examples that show this rule was sometimes flouted by officers; with spikes, badges, buttons and chains sometimes transferred from other headwear on to them. This practice however, can be considered as reasonably rare, and many ornamented ones encountered today have probably been made up after the helmet was decommissioned by the Army.

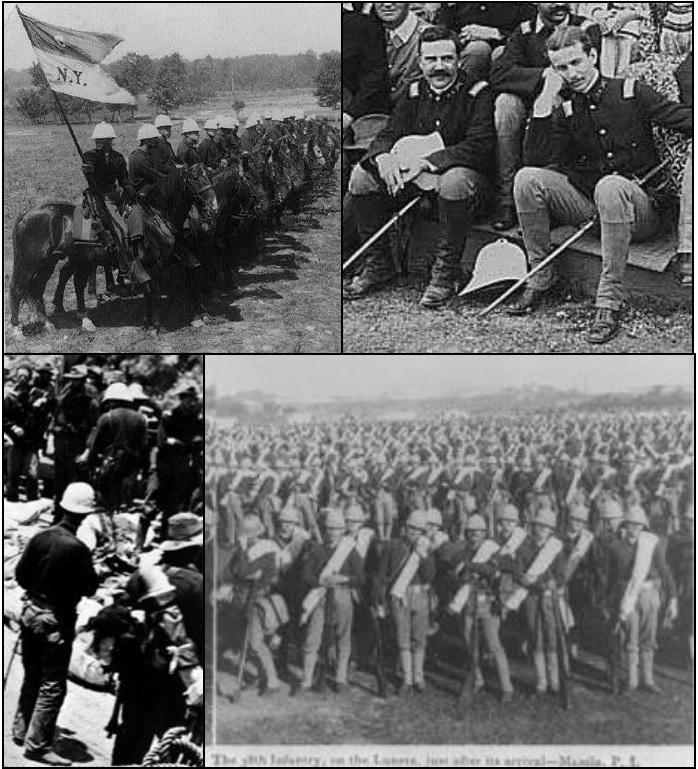

These summer helmets were intended for issue from 1880 onward, with the above changes in design and color at the end of that decade, after which their use became general. They were used during the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars (fig. 3) and during other incidents in the decade either side of 1900. They were, however not popular with troops and it appears its Army use declined in the early 1900s with its issue being discontinued by 1909, with reports of them last being used by American forces in China in 1912 1.

Figure 3. Top left, A New York Militia unit, during the Spanish-American War (1898), wearing M1880 helmets. Top right, Officers or officer cadets during the Spanish American War, with M1887 or M1889 helmets. Bottom left, American troops disembark in Cuba (April 1898). Bottom right, US Infantry after arrival in Manila (1899-1902). These images all appear to be taken during the initial stages of the campaigns, photographs during actual field deployments and actions, however, show the slouch hat was far more popular.

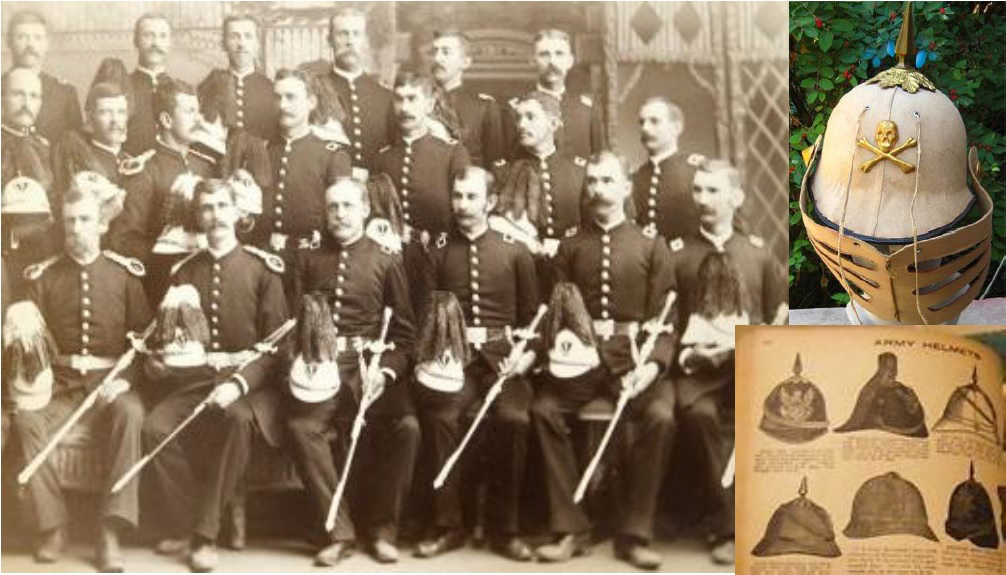

Rather a lot of the helmets appear to have been produced in the couple of decades they were on the books. It is well known that many were then sold off as surplus, most notably to the premier American military surplus dealers ‘Bannerman’ who operated a shop from the 1860s to the early 1950s after which the sold by mail order, until to closing completely in the 1970s. Over the years many of these retired and surplus helmets where bought by individuals, retail shops, clubs, fraternities, lodges and other organizations, who often enhanced them with military surplus spikes and badges etc.; also supplied by the likes of Bannerman, (often as a fantasy package) or with regalia of their own design. A couple of the original manufacturers also continued production of similar styles, selling them to the same customers as above, but also to Militias and some National Guard units during the early C20th.

Many of the repurposed ‘fraternity’ helmets probably had almost as hard a life as those which had been in the Army, seeing regular use at initiations, jamborees and AGMs etc., so these days good condition examples, of either original Army, or the repurposed surplus helmets are pretty rare.

Figure 4. Left, An undated photograph of a Tustin company of the Order of Knights of Pythias. Right, many other groups modified the 19th century military sun helmets. Bottom right, part of a page of the 1929 Bannerman Catalogue.

Featured in Figure 1, is an M1887 which seems to have survived in reasonable condition as it appears to have been part of a number of surplus helmets that remained unsold until; perhaps at the time of the Bannerman’s Broadway (499-501) store’s post war move, or the physical shop’s actual final 1950s closure, they were bought by a professional men’s hatter, ‘Thomas Begg Inc.’ (1930s-1967?), who were actually a Broadway neighbor being at 1427. At Thomas Begg’s they appear to have had simple headbands installed with no spacers, either because this batch had never had them fitted or they showed wear or decay; or it was a method of selling small size shells to people with larger heads? It is not known if the tartan ‘puggaree’ was a Thomas Begg addition or not, but if put together in the 1960s it would indeed follow the kind of trendy styling expected (at least it’s not leopard skin print!) and looking at fig. 7 it would seem large voluminous hat bands were indeed a characteristic of Thomas Begg creations. Also several other near identical examples exist suggesting it was a purveyed style rather than a one off.

Figure 5. Left, A near identical helmet, with the same tartan puggaree from http://www.plundererpete.com/sun-and-pith-helmets. Probably another Thomas Begg refurbishment, Peter Suciu has encountered 4 of these over the years.

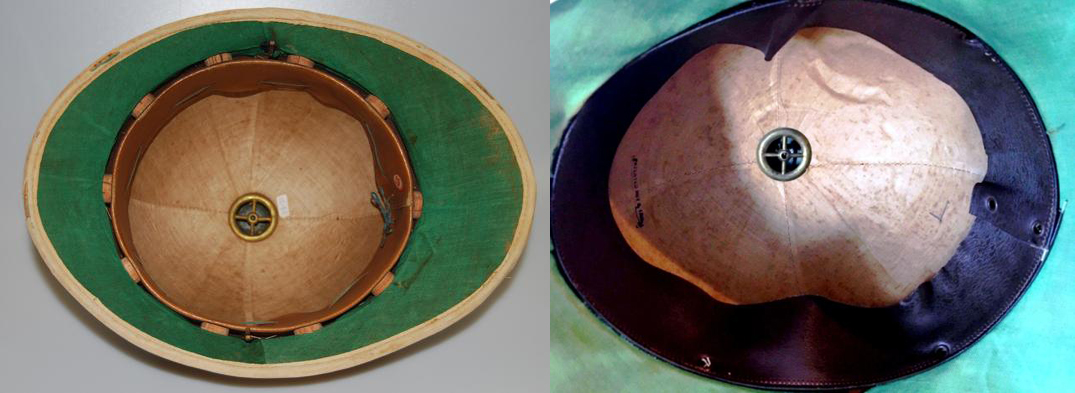

Figure 6. Left, the typical headband found in the 1880 model, with cork spacers; the 1887 and 1889 models were similar, but do not have the draw string. Right, the headband found in Thomas Begg Inc. refurbished ones, a simple riveted on band of thin leather.

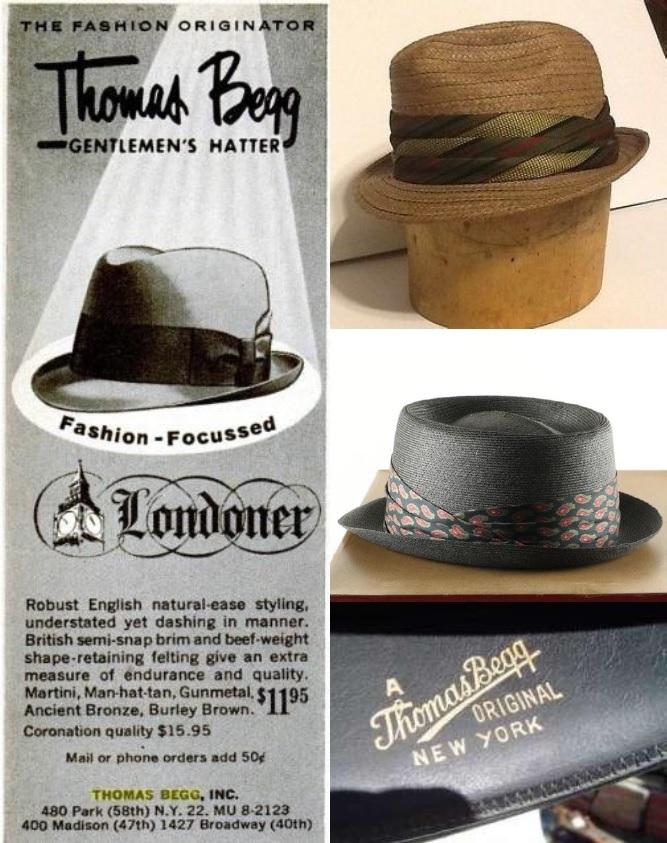

‘Thomas Begg Inc.’ was a chain of hatters with three stores in operation by 1940, that year they began to lease the store in the Metropolitan Opera House building, at 1427 Broadway, New York. They were a famous and fashionable men’s hatter during the 1950s and 60s, producing quality designer hats, which still draw accolades from vintage hat aficionados to this day. ‘Thomas Begg’ was reported as still operating from the Old Opera House in 1965, but by then subsumed under the ‘Hatco’ banner. The building was demolished in 1967 and any evidence of the company’s continued existence has not been found by this author. Unfortunately for the likes of Thomas Begg Inc. the 1960s ‘counter’ culture of individualism not only enabled people to wear none traditional hat styles, but also the choice to not wear a hat at all!

After Thomas Begg Inc., procured this particular helmet in the 1950s or 60s and superficially modernized it, it was sold to a guy called Bob who displayed on a shelf in his living room for many years; after his passing it was advertised on eBay, Spring 2018, by a friend of his wife. Apart from the simple non-original headband, and sixties Ascot style ‘puggaree’, it is in near perfect condition, having not been stained or crushed; pierced or burdened by spurious ornaments, as many others have been.

Its story hasn’t finished; it was lost in the post! Most probably stolen in customs Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, it will probably have a short and interesting life, actually being used as originally intended, as a sun helmet in the settlements!

Figure 7. Left, a 1963 advertisement from ‘Ebony Magazine’, right a couple of typical 1950s-60s Thomas Begg creations. Notice the use of distinctive loose silk hat bands.

Steve Saunders

July 2018

Rabual, PNG

Refences

- Military Sun Helmets of the World, (2011), Peter Suciu with Stuart Bates