The fall of the Portuguese Monarchy, on October the 5th 1910, brought about deep changes in Portuguese military uniforms. The very first measure, taken as early as October the 8th, was the abolishment of the use of royal crowns on the uniforms. In most uniform items, the royal crowns could simply be disassembled, but that was not always so. In buttons, the crowns had to be filed and in helmet front plates, they had to be cut. Most of the surviving helmets keep their front plates complete, so it is likely that this type of headdress was scarcely worn in the early days of the Republic.

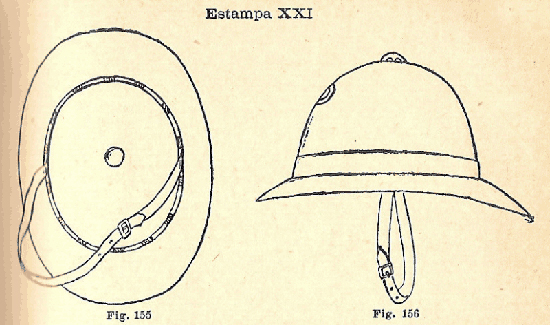

New uniforms were finally adopted by decree of August the 7th 1911. These included a new helmet, officially described as the 1911 model “chapéu” (or “hat”). This new helmet (figs. 1 and 2) was made of stiffened gray felt (in fact, surviving helmets are made of stiffened cloth covered with felt), with a 3 cm wide brim of similar felt around the base of the skull. On the front, these hats were fitted with a 4 cm diameter “Kokarde” with the new national colours (red and green, in replacement of the royal blue and white colours). These “Kokarden” were silk for officers and painted leather for other ranks. The center of the “Kokarde” was fitted with badges or unit numbers (silver for general officers, gilt for officers and brass for other ranks). The peaks had a 30º tilt and they were 5 cm (front), 6 cm (rear) and 3 cm (sides) wide. On the inner side, a sweat-band was placed over 1,5 cm cork discs, providing some air circulation. An hemispheric top, covered in felt and pierced with eight 0,5 cm holes, was placed over the skull. To my knowledge, none of these helmets survived in its original condition, although several “updated models” still exist.

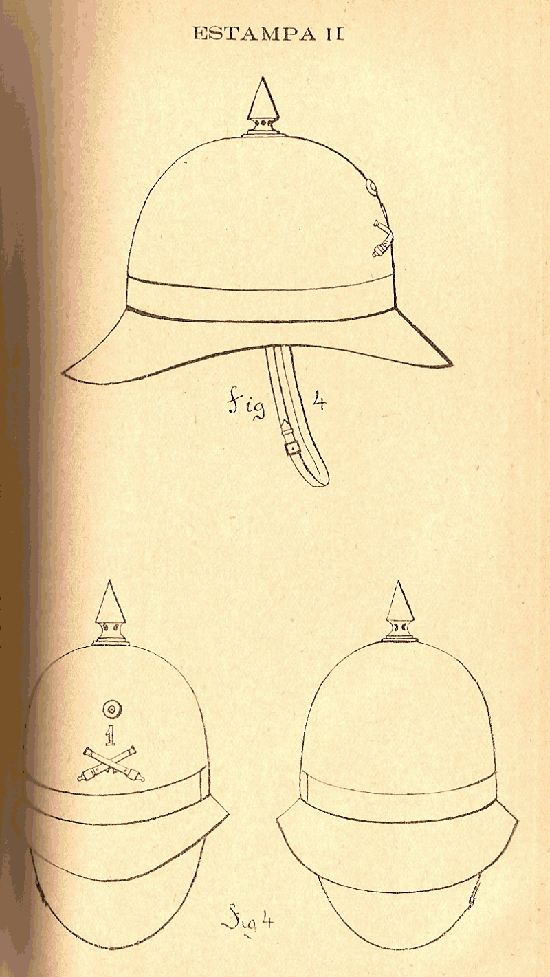

Fig 4: On the left: a 1911 Infantry officers’ helmet “updated” to the 1913 model. Notice the lower skull and the type of construction with felt over stiffened cloth. Also notice the non-pierced metal “Kokarde”. On the right: a 1913 Military Administration officers’ helmet. Notice the blackened metal (copper) spike and the official pressed leather “Kokarde”.

Found to be very expensive, the 1911 dress regulations were deeply modified by decree of August the 23rd 1913. As part of this process, the 1911 helmet was abolished and replaced by a new helmet (fig. 3), officially designated as “chapéu-capacete” (or “helmet-hat”). This new helmet was made of stiffened gray felt, with a blackened copper spike (figs. 4).

Fig 5: A 1913 helmet for other ranks. Note the “field-top” and the soldiers’ number written on the chin-strap. The hatband is missing, showing the metal attachments that secure the sweat-band.

The “Kokarde”, which became much smaller, was made of pressed and painted (red and green) leather, both for officers and other ranks. General officers kept their 1911 badge, a silver five-pointed star, but other officers started wearing blackened metal unit badges or numbers. Other ranks did not wear any unit badges or numbers on their helmets (fig. 5).

Fig 6: A 1913 helmet for a cadet. The letters “EG” on the badge stand for “Escola de Guerra” (War School). This is a fine example of a “Metropolitan” 1913 helmet.

Fig 7: Detail of the sweat-band, stamped “Best London” e “Extra Light”. This type of sweat-band was exclusively worn by officers and cadets.

The 1913 helmet seems to have been produced by two makers only: a Portuguese Oporto firm, “Costa Braga & Filhos” (“Costa Braga & Sons”) and another unidentified (perhaps, but not certainly, British) firm that stamped the sweat-bands “Best London” e “Extra Light”. All the surviving “Costa Braga & Filhos” helmets were issued to other ranks. They are made of coarse felt and bear the Firm’s name on a black, rather crude, sweat-band. All the “Best London”/“Extra Light” were issued to officers or cadets, are made of lighter felt and display much better quality (figs. 6 and 7).

Fig 8: Detail of the official spiked and the semi-official “field top” worn on 1913 helmets. Both were made of copper, as this metal is very easy to blacken. Although the “field-top” was never officially regulated, it was extensively worn.

Apart from the spike, a top of hemispheric shape was used for drill and combat. Although this “field-top” was never officially regulated, it was extensively worn, and at least some 1913 helmets seem to have been issued with both (figs. 8 and 9). It is also likely that the war with the German Empire in Africa contributed to the abolishment of the spike which was, after all, a powerful symbol of the enemy. Whatever the reason, many units involved in the WWI African campaigns never wore the spike. Such was the case of the Naval Fusiliers Battalion sent to Angola in 1914 (fig. 10).

Fig. 10: Officers of the Naval Fusiliers Battalion in Angola, c. 1914. Notice the “field tops” worn. Officers of this unit wore blackened metal anchors over a laurel. Other ranks wore only the anchor.

Besides the official painted leather version, the 1913 “Kokarde” was also produced in at least three other versions: a single piece of stamped and painted metal without piercing, a single piece of stamped and painted metal, pierced in the centre to receive a brass stud and a two-piece stamped and painted metal version (fig. 11). Another change brought about by war was that other ranks started to wear unit badges or numbers on their helmets (fig. 12, 13 and 14).

Fig. 12: A Portuguese soldier, probably of Artillery Regiment n. 4, c. 1915. Notice the 1913 helmet.

Fig. 13: A 1913 helmet for other ranks of Infantry Regiment n. 29, deployed in Moçambique (Mozambique) during World War I. Unit numbers were extensively used by other ranks during the conflict. This is a fine example of an “African” 1913 helmet (Courtesy: Peter Suciu).

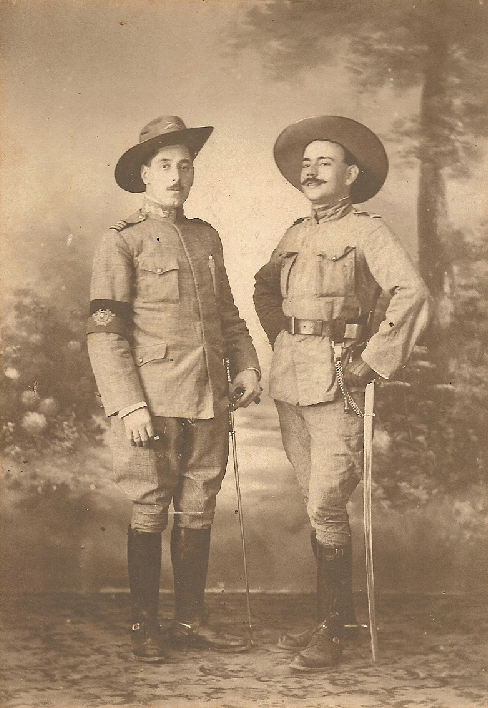

Due to the fact that it was worn in Africa, the 1913 Portuguese helmet may be qualified as a sun helmet. However, it was never intended for tropical use and performed poorly: it was very hot and, even worse, the felt was an attractive meal for many African insects. One must remember that war between Portugal and the German Empire started in Africa in 1914 and that expeditionary forces had to be speedily deployed. This fact is remarkable because war was only officially declared in 1916 and until then none of the enemies even felt the need to withdraw their ambassadors. The 1913 helmet career, as a sun helmet, was short. By 1916, most soldiers in Africa were equipped with much adequate slouch hats (fig. 15). In the Mainland, it was also abandoned and exchanged for the new steel helmets.

Fig. 15: Portuguese Infantry officers (the left one wearing an Army Staff armband) in Africa, c. 1916. Notice the slouch hats.

As collectors’ items, both the 1913 “African” and “Mainland” helmets are exceedingly rare WWI testimonies. If you are lucky enough to have one, keep it safe!

Pedro Soares Branco

Greetings

You say “even worse, the felt was an attractive meal for many African insects. ” But what about the slouch hats? They were not made of felt?

Unlike slouch hats, the 1913 “chapéu-capacete” was made of hardened felt. This implied adding some sort of glue-like agent which was probably the reason insects felt attracted to this type of headdress.

Ah. Ok. Thanks for the reply.