A First World War period British Army issue spine pad. The pad was worn to protect the wearer’s spine from intense heat that was thought to cause heatstroke. (Photo Imperial War Museum, author’s collection)

“The spine pad has become a dull museum piece, and it is probable that specimens are nowadays not easy to find. Yet to those living in tropical areas during the early part of the century and to those serving with the British Army in hot climates during the First World War, memories may be evoked of a piece of cloth of cotton, silk or wool, plain or quilted, several inches wide, attachable to the shirt or coat along the spine, and sometimes with a coloured lining. It is now difficult to accept that this mere piece of cloth could in any way protect from the effects of the sun. But the purpose of the spine pad was so closely linked with the development of ideas concerning body heat, fever and sunstroke, that one must be prepared to explore many early lines of thought for an understanding of its origin and its demise.” 1 So writes E.T. Renbourne , retired Major, Royal Army Medical Corps, in 1956.

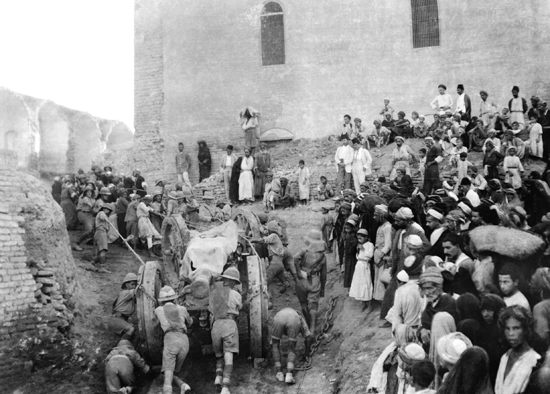

This photo shows Grenadier Guards boarding a river steamer going up the Nile in the Sudan Campaign of 1896 – 1898. Note the quilted spine pads, neck curtains and the red and blue cockades worn on the helmet.

Early in the eighteenth century the Dutch physician Boerhaave wrote on the post-mortem results of sunstroke deaths 2 and for almost a century after this, sunstroke was often confused with apoplexy, but it was generally agreed that in hot climates the important causal factor was the sun. In 1826, John Davy, assistant director of army hospitals experimented with concentrating the sun’s rays through a lens on a cranium using black crepe and interestingly rolled platinum between the lens and the cranium. These experiments, although conducted on a dried skull, may have turned the thoughts of tropical practitioners to the necessity of protecting the head from the sun’s rays. 3

Heat apoplexy (heatstroke or sunstroke in earlier times) is a severe and often fatal illness produced by exposure to excessively high temperatures, especially when accompanied by marked exertion. It can manifest by elevated body temperature, lack of sweating, hot dry skin, and neurologic symptoms; unconciousness, paralysis, headache, vertigo and confusion. In severe cases very high fever, vascular collapse, and coma develop.

Apoplexy was early described as a sudden loss of consciousness, which may be rapidly fatal, may be accompanied by convulsions, and was generally thought to be caused by a cerebral haemorrhage or the sudden blocking of a large blood vessel by a clot (embolism or thrombosis).

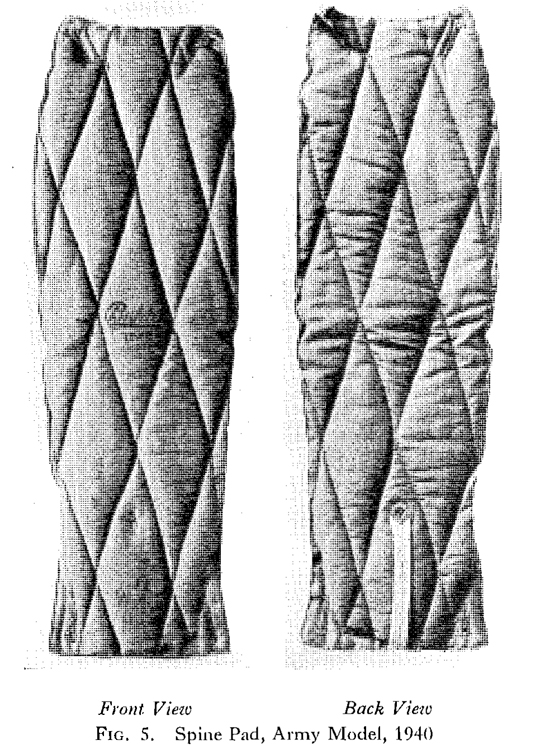

A First World War variation of the spine pad showing the snap fasteners (press studs) which allowed attachment of the spine pad to the soldier’s shirt or coat. An alternative to snap fasteners was the use of hooks and eyes with the hooks attached to the spine pad and the eyes to the rear of the shirt or coat. (Photo courtesy of James Holt)

In the early nineteenth century attention had turned to the spinal cord and theories included that the seat of heat production in the body was the sympathetic nerve which lay on either side of the spinal cord. There was much discussion by medical practitioners and theoreticians but they were not slow in applying the new concepts to the pathology and prevention of sunstroke (as heatstroke was then called.) It was becoming apparent that the brain and spinal cord were in some way concerned with body heat regulation. 4 In 1858 Julius Jeffreys noted that the head was most affected by the sun but that “the spine is also sensitive.” 5 He suggested that for the protection of the spine “We may suspend behind it, at a distance of some inches, an apron or curtain composed of two or three layers of Jean or other doubly woven linen or cotton cloth.” 6

Renbourn states that no evidence has been found for the use of a spine pad of any sort in tropical campaigns up to and including the Indian Mutiny. However, Johnson’s advice [1815] on appropriate clothing became a part of nineteenth century colonial medical commonsense.7 “Henceforth, colonial ‘protective clothing’ meant a light hat or helmet made of pith, a moistened pad of cotton placed on the spine and a band of flannel worn around the abdomen, popularly termed a ‘cholera belt’” 8

Artillerymen in Mesopotamia hauling a 6-inch howitzer and wearing spine pads. (Photo Imperial War Museum, author’s collection)

In 1875 Sir Joseph Fayrer was attached to the suite of the Prince of Wales during his tour of India, 1875 -1876, and he relates “all are provided with light clothing and with quilted pads along the spine.” 9 Renbourn says ”a member of the Royal Family thus wore spine protection thirty-five years before it was issued into the British Army.” 10 Now this is quite wrong as spine pads were worn by the British Army at least as early as 1883 in Egypt 11 and were first “officially” mentioned in the Dress Regulations for the Army 1900, specifically in paragraph 1229 entitled MISCELLANEOUS ARTICLES FOR ACTIVE SERVICE. The spine pad is also mentioned in the Dress Regulations for the Army 1904, paragraph 747, thus “A Spine Protector — A spine protector may be worn when the climate necessitates it.” 12 No mention is made of the spine protector in the 1911 nor the 1934 regulations. It should, of course, be noted that these dress regulations refer to officers only and not other ranks.

This particular khaki vest belonged to an officer serving with the 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry during the Pathan Revolt 1897 – 1898. The vest would have been worn around camp for light duties, as part of his undress, to aid in protection from the effects of the sun and heat. The cloth covered cork toggles affixed to the inside back were intended to keep the garment from resting directly on the wearer’s back thereby by providing some air-flow.

A somewhat humourous anecdote is given by a certain Colonel Maude, an engineer, who asserted that the effects of the sun (actinic, microbial, toxic and caloric) would pierce through anything except a layer of colour, particularly dark red and yellow. He claimed that by adding a lining of orange-red flannel to his helmet, wearing an orange coloured flannel shirt and having an orange-red pad sewn into his khaki coat over the spinal column he never once experienced any bad or distressing effects of the sun. Colonel Maude further claimed further proof when a fellow officer removed the orange-red lining to his helmet and Maude was subsequently “knocked over” by the effects of the sun. He suspected his theory might not be true until the repentant officer owned up to his actions. 12

The first words of this article belong to E.T. Renbourn but perhaps the last should belong to Jack M. Planalp when he says “While Renbourn felt confident in pronouncing a death verdict on the spine pad… it now appears that the matter may not be altogether closed, for R.F. Goldman has told me of recent research by J.D. Hardy at the John B. Pierce Foundation Laboratory in New Haven, Conn, that it is indicative of the possible existence of extra-cerebral thermal receptors along the spinal cord which are sensitive to temperature increments such as those resulting from solar radiation.” 14 It is not within the remit of this article nor the knowledge of this author to comment on this specialist research.

The author would like to express his gratitude and appreciation to James Holt for his assistance in preparing this article.

Stuart Bates

Addendum: The Royal Navy also used spine pads – see here.

1 Renbourn, E.T., The Spine Pad: A Discarded Item of Tropical Clothing, Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, Vol. 102, No. 3, 31st July 1956

2 Boerhaave, H., (1708). Aphorisms, 3rd English Edition, London, 1955.

3 Renbourn, E.T., The Spine Pad: A Discarded Item of Tropical Clothing, Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, Vol. 102, No. 3, 31st July 1956

4 Ibid.

5 Jeffreys, J., (1858), The British Army in India. Its Preservation by an Appropriate Clothing, Housing, etc., London, 1858

6 Ibid.

7 Johnson, James (1815 [1813]) The Influence of Tropical Climates More Especially the Climate of India, on European Constitutions: The Principal Effects and Diseases Thereby Induced, Their Prevention or Removal, and the Means of Preserving Health in Hot Climates, Rendered Obvious to Europeans of Every Capacity. London: J. Callow

8 Sen, Indrani, Memsahibs and Health in Colonial Medical Writings, c. 1840 to c. 1930, South Asia Research Vol. 30, 2010

9 Fayrer, J., Recollections of My Life, London, 1900

10 Renbourn, E.T., The Spine Pad: A Discarded Item of Tropical Clothing, Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, Vol. 102, No. 3, 31st July 1956

11 Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, Vol. 83, July 1990

12 Dress Regulations for the Army 1904, HMSO, 1904

13 Bricknell, M.C.M., Heat Illness – A Review of Military Experience, Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, Vol. 141, 1995

14 Planalp, J.M., Heat Stress and Culture in North India, US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, 1971

great information on a unusual subject

I’ve wondered , on off, over the last 70 years why spine pads where worn by British soldiers serving in hot countries during the 1920s, at least for some of the time my father was in Indian and mesopotamia i.e 1921-1928. Thank you to all those who contributed to the very detailed information and especially the pictures.

Dear Mike,

thanks for your comment and I wonder whether the “science” of spine pads has moved forward as alluded to in my last paragraph.

I wonder if you have any relevant photographs of your father in Mesopotamia which I could use to update this article.

Best regards,

Stuart

According to my parents, who lived in Singapore before WW2, spine lads were considered essential to protect the spine from the tropical sun. Ordinary clothing, even if opaque to the eye, was not enough. My father was captured and spent the Occupation years in the Siam Road and Changi prison camps, where spine pads ( and the equally vital pith helmets) were not available. No ill effects were noticed, and after the war both spine pads and pith helmets ceased to be worn.

Pingback: Royal Navy Tropical Flannel | Tales from the Supply Depot

Hi Tom,

thanks for the information it all adds to the sum of knowledge.

Regards,

Stuart

I have added an addendum as a reader informed me that the Royal Navy also used spine pads.

I am reading a 1939 book about a Western man’s travels through Syria & Arabia to Persia (‘By Camel and Car to the Peacock Throne’) in which the author wrote “The British troops in Mesopotamia are required to wear spine-pads…”.

I had to see what those were & found your description & photos. Thank you!

Of course they could have simply paid attention to what the indigenous people were wearing (like many visiting & occupying Orientalists did prior to the invention of these “spine-pads”). But that would have meant acknowledging the greater wisdom – regarding the locals own lives & affairs – of the indigenous people there.

This is just so funny to me (confession: I am half Lebanese). The last thing you want to put on is layers of heavy quilting. The main thing is to stay out of the sun at midday. And people like the Bedouin & Tuareg etc. – if they had to/have to travel in the sun – shield their skin w/ loose breathable layers.

Who came up w/ the line ‘Only mad dogs & Englishmen go out in the midday sun’ ?

Yes it seems odd to us today and back then, but Western science was paramount for the Western world.

I often wonder at the U.S. Cavalry wearing kepis during the Indian Campaigns and the kepi being so ubiquitous in their Civil War.

I suspect you know the originator of the quote you mention.

Regards,

Stuart

Thanks for your reply. I’ve since looked up the phrase ‘Mad dogs & Englishmen…’ & its origin is the title & lyrics of a Noël Coward song from the 1930s. I did not see that coming! I should have known that because a house in my town (one hour from NYC) that he owned w/ his manager – which they summered & entertained in – went on the market in 2015. (Obviously I need to brush up on my local Noël Coward history!). Some think he got the idea from something Kipling wrote re. British in India. (From a Kipling passage that looks nothing like the Noël Coward song title/lyric).

Regarding the U.S. Civil War & Indian wars caps you wrote of – you’ve reminded me – only months ago I gave an 1874 issue of Bazaar (American magazine/then newsprint paper) to our local indigenous Mohegan Nation (tribe). They have a museum & library which contains various indigenous American objects. I gave it to them because it contained contemporary (c.1874) articles w/ illustrations on the ‘Modac Wars’. Specifically re. U.S. troops killed. (Obviously not focusing on indigenous killed). The soldiers in the illustrations were wearing the caps you described. I was not aware of the name for those. Thanks for your info. I have an interest in vintage & antique dress.

Sorry Zoé but I simply assumed that you were aware that it was Noël Coward.

Stuart

That was fine! (re. Noël Coward). I had only known of the late 1960s/early 70s musician Leon Russell & his album ‘Mad Dogs & Englishmen’ in my dad’s collection. (Name of his travelling supergroup then & thus the album).

Btw though the book I was reading was published in 1939; the author’s travels seem to have taken place in the 1920s. (I was going through my phone now & realised I never clarified that). You probably already gathered that; from knowing when these ‘spine pads’ were in use.

Also regarding those U.S. Civil War caps (Kepis – as you called them – a term you’ve taught me!); I recall seeing photos of women in the late 19th c. wearing fashionable ‘toy’ versions. (‘Toy hats’ in fashion meaning those tiny hats usually worn on upswept hair & which have been going in & out of fashion for centuries).

Lastly – I misspelled ‘Modoc’ (Indigenous N.American tribe I mentioned above re. illustrations of Civil War/Indian Wars kepis). My apologies to the people themselves.

Thanks again for your fascinating site!

It’s a song by Noel Cowerd

https://youtu.be/eNTeQkSkc18

The U.S. military also had a form of insulation in the upper back area of their early issue “chocolate chip” Desert BDU top (DBDU). It was an extra layer of fabric that stretched from the base of the collar, across the shoulders, and about to mid-back, on the interior of the shirt/jacket/blouse. When issued those in the early 1990’s in the US Army, we would typically cut them out to make the top breather better and used the material for repairs or making stuff out of.

Hi Steve,

that is fascinating. Do you have any photos?

Stuart