An interesting and rare example of an officer’s Colonial pattern Foreign Service Helmet showing the neck curtain secured by an elastic strap. (Photo courtesy Benny Bough)

“From the earliest times fear of the sun’s rays must have sometimes urged the soldier or traveler to wear down the back of the neck a white handkerchief or handy piece of cloth. The official introduction of a neck curtain, however, appears due to Sir Henry Hardinge, who, in 1842, prior to leaving for India as Viceroy, ordered white cap covers for tropical use, to which was added some time later a white neck curtain.” 1,2

This painting of the assault of Mooltan, 1849, clearly shows two officers wearing white cap covers with white neck curtains but also shows an officer wearing a dark neck curtain. 3

Within a few years the Sikh Wars had broken out, and old prints of battle scenes show that a white cover and neck curtain for the shako and forage cap were in use at the battles of Ferozeshah (December 1848) and Mooltan (January, 1849) during the hot days of the winter season.

The frequent use by General Havelock, in India, of the combination of a white cap cover and neck curtain for his troops no doubt led to his name being associated with this form of headgear and records of the “King’s Own” contain the following order of 1858: “Wicker helmets covered with white cotton to be worn with puggarees with ends hanging down as a curtain.” 4

The Queen’s Bays (2nd Dragoon Guards) charging at Lucknow. Note the puggarees, with “tails”, tied around the brass helmets.

Cavalry wore their brass helmets with a puggaree wound around the base of the crown with “tails” flowing down the back or had a cover complete with a neck curtain. Heatstroke took an enormous toll, especially in the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 and Richard Collier writes that “On May 27th the Horse Artillery had left Meerut stifling in brass helmets, tiger-skin rolls, cloth dress jackets with high red collars, leather breeches and high jack-boots.” 5 Only the unorthodoxy of their commander, who ordered them to rip off their collars, saved them from severe heat casualties.

An alternative to this arrangement of a puggaree wound around the brass helmet was a quilted helmet cover with a detachable neck curtain.

An example of a helmet to the 1st King’s Dragoon Guards complete with quilted cover and neck curtain. Although the regiment was in India at the time of the Mutiny it does not seem to have been involved in the fighting. (Author’s collection)

Neck curtains were worn by the forces of nations such as France and Germany with “reference to the early interest in the neck curtain by the French Army being given by Martin, who in 1859, noted that Scouttenten of Algeria was at that time pre-eminent among French physicians in urging the necessity for its use.”6 Judée in 1863 was instrumental in introducing the couvre nuque or neck curtain into the French Army.7 The German military hygienists, Roth and Lex, were great admirers of the British clothing and equipment, and in 1877 commented on the Nackenschurz or neck curtain as follows: “The simplest protection consists of the white cover and neck curtain of the forage cap. This was first used in 1842 by English troops serving in India.”8 However, in 1899 Captain Freeman, R.A.M.C., noted that a quilted curtain at the back of the neck has sometimes been used on service, but is very heating on the neck.9 Nevertheless a neck curtain continued to be used by the British Army in most tropical campaigns.10

Private Byrne, VC, 21st Lancers wearing an extremely large neck curtain over his Colonial pattern helmet. This curtain went over the crown of the helmet and had no other method of securing it.

Neck curtains were never officially recognized until the Dress Regulations for the Army of 1900, which in paragraph 1197 stated “A detachable khaki helmet curtain may be worn when the severity of the climate necessitates it.” This is a classic case of the “horse having bolted” as will be appreciated from the preceding narrative. The neck curtains were not mentioned in the Dress Regulations for the Army of 1904 but continued in use during the inter-war period.

A cover with neck curtain for an officer’s field service cap as worn by the 2nd Volunteer Battalion, The Gloucester Regiment c.1880-1890. Note that the neck curtain is an integral part of this item. (Photo courtesy of the Soldiers of Gloucester Museum)

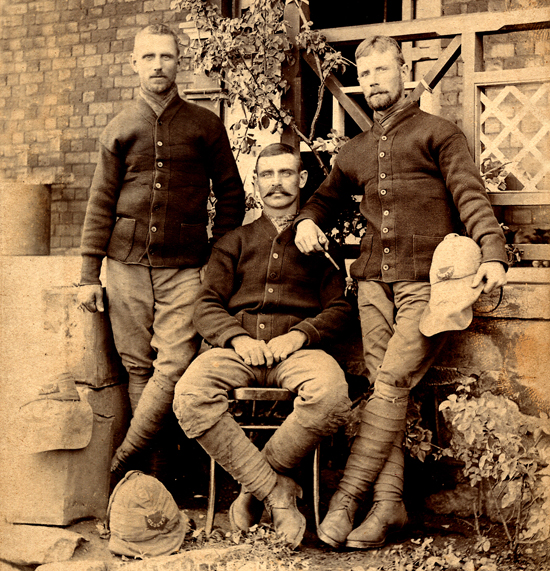

This photo of three soldiers of the Gloucester Regiment clearly shows the neck curtains attached to the helmets as well as the famous back-badge, in this case a flash. (Photo courtesy of The Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum)

Neck curtains were normally attached to the helmet by a cotton tie stitched to the neck curtain but as can be seen from the opening photograph elastic was also used, as were hooks and eyes to affix the curtain to khaki cloth covers. The above photo of the Gloucestershire soldiers’ helmets would indicate that the neck curtain is tucked under the puggaree and, indeed, in an Osprey book 11 there are illustrations showing exactly this, but this author finds it difficult to accept that such a method was used. To have to remove and refit the puggaree whenever the neck curtain was fitted or removed seems an unwieldy practice. It is possible that the neck curtain is an integral part of the khaki cover such as shown in the photo of the cover and neck curtain for the field service cap. However it is more likely that the neck curtain is attached by hooks and eyes directly to the khaki cover and just under the puggaree.

Soldiers wearing the Home Service Helmet with khaki cover and neck curtain during the Boer War. Note especially the leather chinstrap which was fixed to the rose bosses underneath the khaki cover.

“The Home Service Helmet was used in South Africa as the Foreign Service Helmet was in short supply after 1900. The covers that were supplied for them had a removable neck curtain affixed to the cover and held in place by hooks and eyes, though some were permanently stitched to the bottom of the cover itself.” 12 Since the Home Service Helmet was criticized for its lack of ventilation on home service duty it must have been rather uncomfortable on active service in South Africa during the hot months of the year. It should be noted however that examples of Other Ranks’ Home Service Helmets often have “corrugated” cork inserts between the headband and the shell.

The neck curtain here is fixed to the khaki cover by means of hooks and eyes, the hooks being on the curtain and the eyes on the cover just underneath the puggaree. (Photo courtesy of James Holt)

Here the neck curtain is tied onto the helmet and over the khaki cover. (Photo courtesy of James Holt)

This would appear to be an improvised neck curtain fitted to this Australian soldier’s slouch hat. An interesting addition since the slouch hat was widely regarded as providing good sun protection.

This photo shows a neck curtain and goggles fitted to a Wolseley helmet to the Warwickshire Yeomanry. Note the quilted finish of the neck curtain.

Goggles were issued at least as early 1885 during the Suakin Campaign as the following description details. “The men had all to be fitted with their kharkee kit and served out with their cholera belts, goggles, spine-protectors, and veils. It certainly seemed as if the people at home had determined no pains should be spared to protect the soldier against the climate and the sun, although we on our side felt bound to confess that when we appeared in full battle array we resembled a number of perambulating Christmas-trees more than anything else.” 13 The arrival of the Guards for Kitchener’s Sudan Campaign is described by G.W. Steevens thus: “Falling in beside the train they were certainly taller than the average British soldier but hardly better built. They were mostly young, mostly pale or blotchy, and their back pads – did you know before that it was possible to get sunstroke in the spine? – were sticking out all over them at the grotesquest angles. Many of the officers wore thick blue goggles, and their back pads were a trifle restive too.” 14

Again with the Australian Flying Corps in Mesopotamia, 1915, goggles were issued. “The heat in Mesopotamia is intense, and, owing to the swamps and the myriads of mosquitoes, malaria and other tropical diseases soon appeared… Cases of sunstroke were frequent, and all ranks were supplied with spine-pads and dark glasses for protection against the rays of the sun.” 15 From the same source it appears that the goggles were less than effective in keeping out sand during a sand storm as were the veils provided for such events and to provide protection from flies.

Stuart Bates

1 Renbourn, E.T., The Spine Pad: A Discarded Item of Tropical Clothing, Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, Vol. 102, Oct. 1956

2 Parkes, E.A., (1864), Manual of Practical Hygiene prepared especially for use in the Medical Services in the Army, London.

3 Mainwaring, Arthur Edward, Crown & Company, Arthur L. Humphreys, London, 1911

4 Cooper, L.I. (1939), The King’s Own. The Story of a Royal Regiment, Oxford

5 Collier, Richard (1964), The great Indian Mutiny;: A dramatic account of the Sepoy Rebellion, Dutton

6 Martin, J.R. (1859), Lancet

7 Judé3, M. (1863), Spectateur Militaire, 15 Février

8 Roth W., & Lex, R. (1877), Handbuch der Militar-Gesundheitspflege, Berlin

9 Freeman, E.C. (1899), The Sanitation of British Troops in India, London

10 Renbourn, E.T., The Spine Pad: A Discarded Item of Tropical Clothing, Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, Vol. 102,

11 Wilkinson-Latham, Robert, The Sudan Campaign 1881-98, Osprey Publishing, Oxford U.K., 1976

12 James Holt in conversation with the author after viewing such a helmet.

13 Parry, Ernest Gambier (1886), Suakin, 1885 Being a Sketch of the Campaign of that Year, Keegan Paul, Trench & Co., London

14 Steevens, W.G., With Kitchener to Kartum, Dodd, Mead & Company, 1898

15 Cutlack, F.M., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914 – 1918, Vol. 8

Nicely written and presented. Thankyou for an interesting article on neck curtains

until i read this i knew nothing about neck curtains keep up the good work

have read all your articles and they are all great. congratulations for hard work on this website.

Hi, Great article. I’m particularly intrigued by the picture with the goggles on the Warwickshire Yeomanry helmet. These look identical to a pair of goggles my Father was issued in North Africa in 1941-42, although he never had a pith helmet. He gave the goggles to me in the 1970’s and I subsequently lost them. To compensate I’ve bought three pairs in the last year! They have SLM and the manufacturing date on them, one 1940 and the other two 1942. Do you have any details of the type? Who were SLM and when were they first made? I’ve read they may have been about in the First World War, was the tooling hurriedly put back into production in early 40’s when war in the desert looked likely?

Regards

Steve

Hi, Great article. I’m particularly intrigued by the picture with the goggles on the Warwickshire Yeomanry helmet. These look identical to a pair of goggles my Father was issued in North Africa in 1941-42, although he never had a pith helmet. He gave the goggles to me in the 1970�s and a subsequently lost them. To compensate I�ve bought three pairs in the last year! They have SLM and the manufacturing date on them, one 1940 and the other two 1942. Do you have any details of the type? Who were SLM and when were they first made? I�ve read they may have been about in the First World War, was the tooling hurriedly put back into production in early 40�s when war in the desert looked likely?

Regards

Steve

Sorry Steve but I haven’t done anything on goggles. I used that photo because it so beautifully illustrated the neck curtain.

Would you care to write an article on goggles as we are always keen on getting new contributors?

Cheers,

Stuart

Hi Stuart , if I find anything out I’ll let you know. I know SLM also made some of the larger hinged teardrop goggles standard to British and Commonwealth forces early 1940’s

Are these goggles original to that helmet?

Regards

Steve

Steve,

The owner would have me believe so but it is doubtful.

Regards,

Stuart

Could you ask the owner if they are marked? I know WWII ones are, on front of frame. If not could early ones?

Regards

Steve

Steve,

I don’t know whether he still has it as he offered it to me anyway you could try contacting him via his website http://militaryorphanpress.com/Military_Orphan_Press/Contact_Author.html where the same photo is used.

He and I do not get along these days.

Regards,

Stuart

Thanks have emailed him. I’ll let you know what happens.

I have been writing a piece on a type of goggles and would be happy to have it on your Web site. But not sure if appropriate? Could I send a pdf of a draft and you let me know?

Regards

Steve

Hi Steve,

sounds good! When ready send me the PDF via email stuartbates[at]bigpond.com

Regards,

Stuart

Pingback: Spotlight: Bushranging at the Billabong – A Guide to Australian Bushranging